|

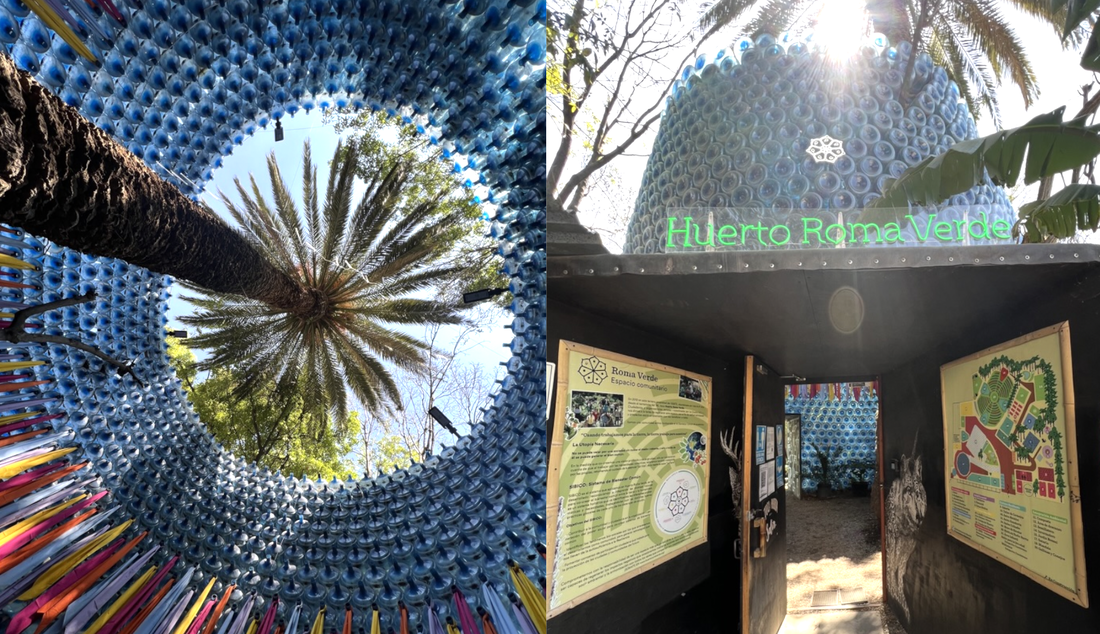

Community gardens, urban farms, and public edible landscapes infuse fresh food into our city lives, grounding us in the natural world and its seasonal rhythms. However, these spaces often come with barriers: big fences, locked gates, and a sense of exclusivity that can make nearby residents scoff, “Community garden? Not for me.” But inside, there’s a different story. Those who tend the plots are often deeply connected to the neighborhood, though a clear divide exists between them and those left outside. We see placemaking as a game-changer in the world of urban agriculture and community gardening. It’s about breaking down barriers and welcoming more people in, especially in low-food-access neighborhoods where a garden could revolutionize local health and social safety nets. Transforming Spaces: Tips for Urban Ag Sites1. Rethinking Boundaries: The Art of Fencing Yes, gardens indeed need fences—to shield them from hungry animals that could ravage a garden overnight and to deter the occasional vandal or uninvited gleaner. Yet, some fences we see are so imposing they seem to scream "food maximum security" rather than "food security." Here's how we can turn barriers into welcoming features: Embrace Living Fences: Cultivate a fence with a purpose. Planting blackberries or other vine crops can transform a stark fence into a lush, living boundary. It becomes a beautiful hint of the bounty inside and extends an open invitation for passersby to enjoy a summer berry and perhaps, strike up a conversation with the gardeners. Strategic Setback: Sometimes, it's not just what you plant but where you place it. Many gardens push their fences to the very edge to maximize space. However, setting the fence back even just a bit can create a welcoming 'front yard' effect. This space can serve as a mini public square, offering benches, a spot for food sharing, or a communal herb garden with mint or rosemary for anyone to harvest. By reimagining how we delineate our garden spaces, we can foster a sense of openness and community while still protecting the fruits of our labor. Try setting the fence back. It’s a simple trick that creates a welcoming front yard vibe, offering space for food sharing, seating, or public herb gardens. 2. Crafting the Welcome Artful Entrances: The entrance should be a testament to the garden's ethos, inviting curiosity and interaction. An attractive sign or archway that captures the essence of the garden can intrigue and draw in visitors, setting the tone for the experience within. Informative Displays: Clarity invites participation. A well-designed welcome area should offer essential information at a glance – opening hours, contact details, and upcoming events. This openness not only encourages community involvement but also integrates the garden into the rhythm of neighborhood life. Neighborhood Signage and Wayfinding: Effective wayfinding ensures that the garden is a community fixture, not a hidden secret. Signs placed throughout the neighborhood can guide residents and visitors to this verdant haven, making it an accessible destination for all. Consider maps, directional arrows, and even digital markers for those using smartphones to navigate. 3. Programming and Open House: Cultivating Community Through Activity Urban gardens are more than plots of land for cultivation; they are vibrant community centers that offer a remedy to the mental health crises and isolation prevalent in today's society. To truly flourish, these spaces must provide a variety of reasons for people to gather, connect, and engage beyond the care of their garden beds. Wellness and Recreation: Activities like yoga, including popular variations such as goat yoga, invite people to unwind and connect in the serenity of nature. These sessions offer a dual benefit: promoting physical health and creating a communal rhythm that resonates through the garden. Direct Engagement with Nature: Initiatives like 'U-Pick' events and farm stands do more than just provide fresh produce; they invite hands-on interaction with the garden's bounty. This direct engagement is a tangible way for community members to support the garden's sustainability while enjoying the fruits of their labor. Community Exchanges: Our 'Crop Swap' program is a testament to the power of sharing. Over eight years, participants have exchanged over 14 tons of produce, seeds, and gardening insights, fostering a rich tapestry of communal knowledge and culinary diversity. Open Hours and Amenities: By opening the garden for regular visiting hours, offering volunteer opportunities, or simply providing a space where one can work remotely with the added benefit of free Wi-Fi and garden-grown herbal tea. Mixing uses by adding a mobile book shops or flower store, can transform these green spaces into hubs of community life. In essence, gardens are not just about cultivating food; they're about cultivating community. PlacemakingUS recognizes the profound potential that lies in each urban agriculture site. Through our dedicated efforts, we visit and assist gardens in realizing their fullest capabilities, transforming them into vibrant, communal spaces that extend far beyond the confines of cultivation. We are committed to collaborating with local food communities, bringing the wisdom and practices of placemaking to these essential urban spaces. Our work is more than a passion—it's a critical step toward a more sustainable society. By enhancing these gardens, we contribute to carbon sequestration, reduce food miles, and strengthen the fabric of our communities, creating spaces of social cohesion and comfort. Aligning with the universal principles for sustainable development advocated by UN-Habitat, we believe in nurturing spaces that foster a deeper connection to our environment and each other. We invite you to join us in this transformative journey, reshaping our urban landscapes into thriving, sustainable, and inclusive communities. Article and Photos by Ryan Smolar, Co-Director, PlacemakingUS

0 Comments

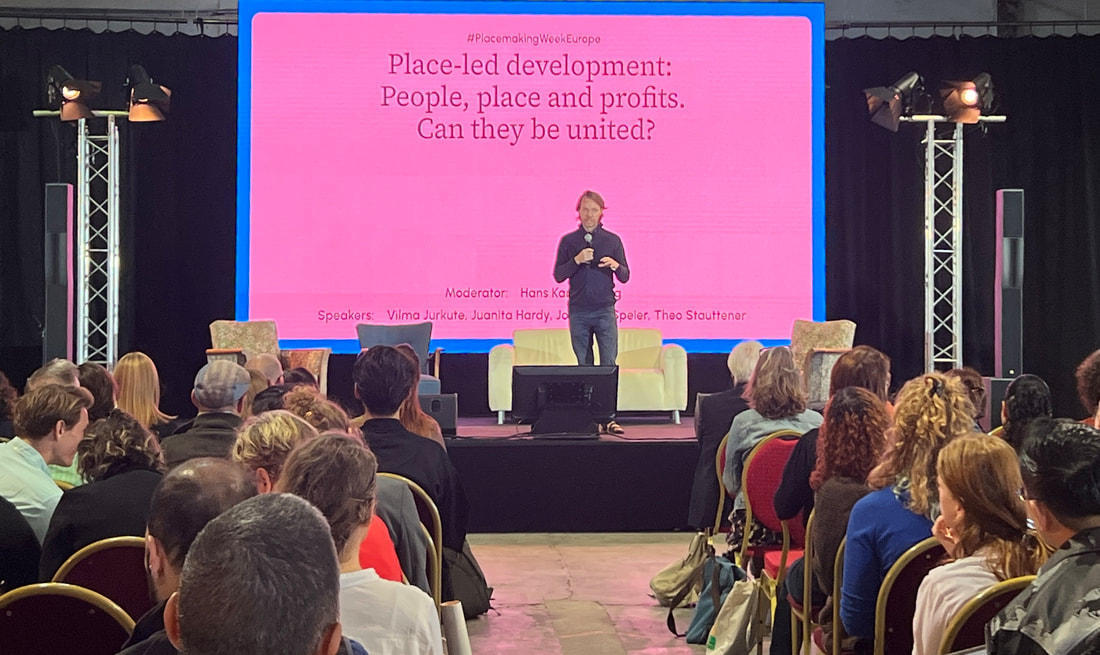

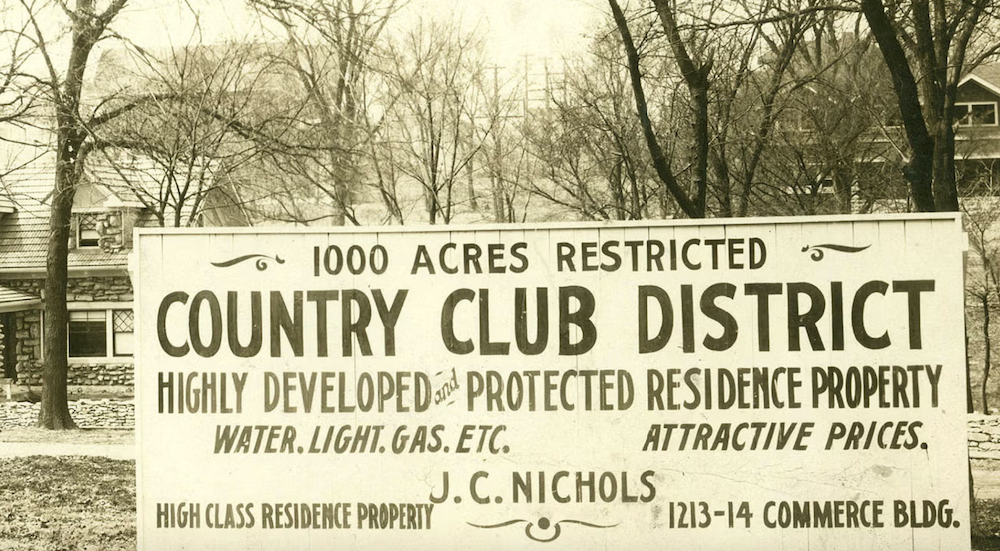

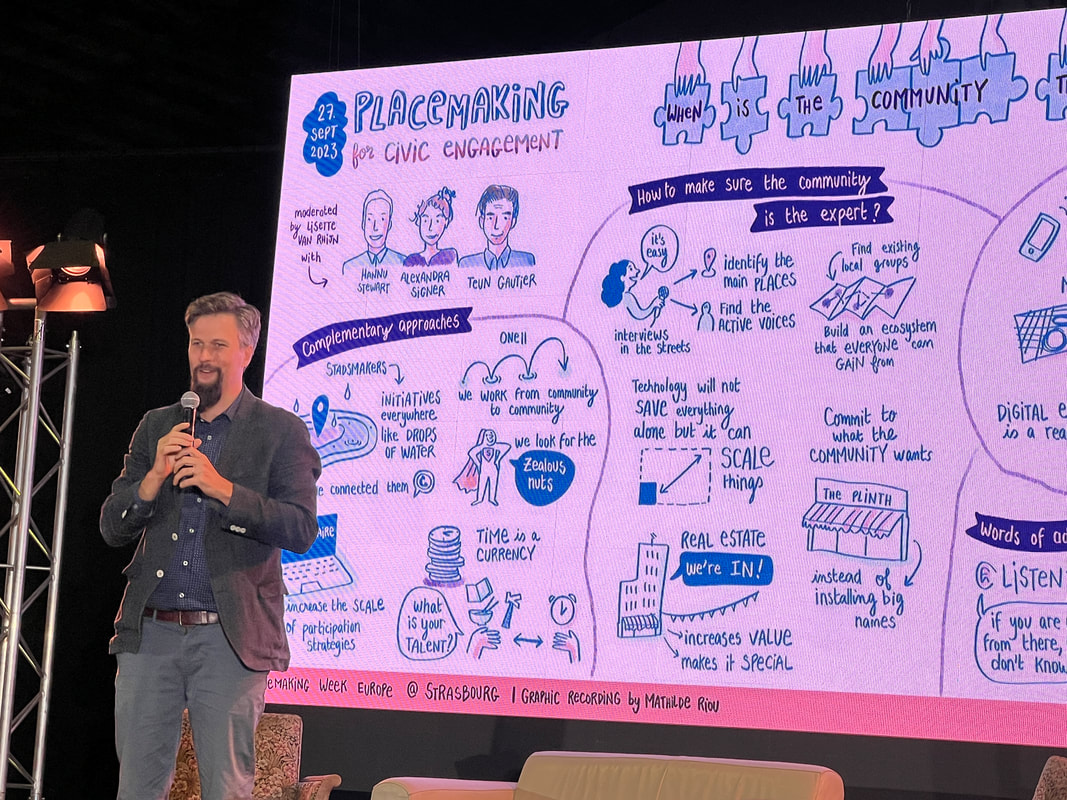

Placemaking, a term with noble intentions in the realm of urban development and community-building, is at risk of losing its true essence. As we grapple with the ambiguity surrounding this concept, there is a pressing need to define placemaking and defend it. Without a clear definition or underpinning principles, the term becomes vulnerable to distortion, manipulation, and misappropriation by commercial and political entities and the uninformed. In this article, we delve into the critical importance of upholding what we mean by the word, 'placemaking' and the consequences of allowing the term to be used willy-nilly. A Most Meaningless Word Recently, an article in Dezeen created ripples within our placemaking community with its deliberately provocative headline: "I have a confession to make: I have no idea what placemaking is." The piece aimed to make a stir and ignite debate, cited the ambiguous language often used to describe the multi-faceted subject by quoting at length from Project for Public Space's lofty explanations of the concept. Unfortunately, the fine-buttered words and finessed phrases from their website do seem to paint placemaking as a panacea that sounds suspiciously like the snake oil salesman's remedy for cities. In response to the grenade Dezeen threw into the room, the co-director of Placemaking Europe penned a response entitled, "I have a confession to make: I don’t care what placemaking exactly is." His article argues that delving into semantics is a futile endeavor when placemaking appears to be an overarching term encompassing individual, positive actions aimed at enhancing our urban spaces. While, in my heart, I'm inclined to agree, this philosophical stance raises concerns—especially for a group that recently brought together 500 placemaking practitioners and eager learners, providing them with content that sought to define placemaking through speeches and interactive workshops. A precarious panel on placemaking at Placemaking Week Europe 2023 in Strausborg, France. The Dangers of (Mis)Defining Placemaking At the Placemaking Week Europe event last month, I found myself stunned at what was being described as placemaking from their main stage. During a talk entitled, Place-Led Development - People, place, and profits. Can they be united? an elderly woman of color named Juanita Hardy, who is the Senior Visiting Fellow for Creative Placemaking for Urban Land Institute, had this to say: "Placemaking started in the United States in the 1920s when a developer in Kansas City built a successful shopping mall 4 miles from the downtown heart." Besides what sounds obviously wrong with that statement, I knew as one of the few Americans in the room who's been to Kansas City several times that she was referring to County Club Plaza and its creator, JC Nichols. While Country Club Plaza is a charming piece of faux urbanism with a mix of automobile access, walkability, and even great programming, this project is more notably the development where suburban racial segregation took root in America. A recent article in Slate called, "The Made Who Made the Suburbs White" more accurately describes the Country Club District, not for its placemaking principles but for its pioneering of the use of racial covenants: not allowing minorities to rent or buy in the district. The Country Club's "protected" district was a progenitor of the racially-segregated suburbs. Photo courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri To quote the Slate article at length: "In the 1930s, the Nichols Way received a boost from the federal government...To Kevin Fox Gotham, a professor of sociology at Tulane University and author of Race, Real Estate, and Uneven Development, it seemed as if the Federal Housing Authority had “adopted [Nichols’] methods and practices almost verbatim.” This means there is a strong connection between the racial covenants that JC Nichols pioneered with the federal practice known as redlining, which segregated and destroyed black neighborhoods across the country. JC Nichols should be remembered as the father of racial strife, white flight, and our national inequities, but not the father of placemaking without the caveats that we now have federal laws like the Community Reinvestment Act and Fair Housing Act to protect people who look like Juanita and me against the ideas and actions of men like him. The Line is a futuristic, 'sustainable' megacity project in Saudi Arabia that aims to create a 170-kilometer-long, car-free urban development in the desert. The project has produced a mini-series calling the architects, planners and futurists associated with the plop project as "The Line's Placemakers." Letting Commercial Interests and Professionals Define Placemaking In 2021, PlacemakingUS was approached by Ph.D.'s at the research department of a global architecture firm asking us to endorse a report they made to educate their 1,000 employees on "The Subtle Art of Placemaking." But after reading it, I had to write them a pointed rebuke that their report should rather be called "The Subtle Art of Placebaking," i.e. taking the ingredients of placemaking and utilizing them in a measured, professional and controlled way to bake a pre-packaged "place cake." Notably because their guide lacked any mention of co-design or community participation, failed to explore the use of the temporary to inform permanent solutions, neglected discussions of sustainability and equity, and omitted fundamental concepts like the mixing of uses. Another group, the International Downtown Association (IDA), has recently become an accrediting organization. They have introduced the suffix "LPM" to designate "Leadership in Place Management" to those bold enough to pass a 100-question multiple choice test. One of the core domains of knowledge for this accreditation is about placemaking expertise. While the information promoted by IDA maintains high quality and is crowd-sourced, it is primarily driven by the commercial interests of individuals representing business and property owners. I've encountered numerous business improvement districts (BIDS) whose idea of placemaking is constructing outdoor ice skating rinks in arid and subtropical regions of the United States. While these novel gimmicks inject fun and vitality into cities, they often disregard the fundamental principles of sustainability, including water use, energy consumption, non-renewable materials, and transportation costs on the environment. These projects reveal the trend that BID placemakers are often just re-branded marketing/events staff whose motivations are to follow trends and attract customers, rather than to ensure that the city remains accessible for everyone to contribute creatively. Kady Yellow, a distinguished practitioner, bucks this trend by demonstrating that a BID-embedded placemaker can serve as a powerful catalyst for driving systemic change and amplifying diverse voices. Through her roles as the Director of Creative Placemaking in both Flint, Michigan, and Jacksonville, Florida, she has illuminated the transformative potential of resident-led placemaking programs within business districts. Her initiatives not only educate the community about their role as placemakers but also provide essential funding and leverage the BID's unique privileges, granting access to permits, spaces, and relationships for collaborative city-building. Similarly, Richard Amore at the Vermont State Department of Commerce worked with his state legislature to create crowd-matched funds to make community-led and supported placemaking initiatives more accessible through the a 2:1 match of local funds raised for their own ideas to make their communities into Better Places. A business improvement district building a temporary, outdoor ice skating rink in sunny Southern California as a "placemaking" project. This wood was cut just for the project, but boosters say it will be re-used for 5 winters. To Define AND Defend Ethan Kent, leader of our PlacemakingX global networks, often upholds the ooey-gooey consistency of the made-up word placemaking saying there's great power in letting people define placemaking for themselves and the plasticity of the definition lends to the field's necessary adaptability. As an idealist, I agree, but the realist side of me recognizes that as we let placemaking blow in the wind, other interests are defining it and giving it a bad name such that many low-status communities now prefer the term placekeeping, that is keeping the so-called placemakers away so that the neighborhood can continue to exist without cultural and physical displacement. This issue takes many forms, as even our sister network, Placemaking Collective UK, is considering changing their name to be called the Place Collective UK, due to the perceived 'wonkiness' of our term. They were advised to keep placemaking in their name, yet another network, Peacemakers Pakistan, has struck a unique balance by alluding to placemaking while adapting their name to the most relevant challenges and opportunities of their context. A good example of the need to define and defend placemaking can be illustrated by the National Endowment for the Arts-funded white paper "Creative Placemaking" published by Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa in 2010, which set the stage: "In creative placemaking, partners from public, private, non-profit, and community sectors strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood, town, city, or region around arts and cultural activities. Creative placemaking animates public and private spaces, rejuvenates structures and streetscapes, improves local business viability and public safety, and brings diverse people together to celebrate, inspire, and be inspired." This report, which has been cited nearly 700 times in further works, helped define that field and resulted in over a hundred million dollars of investment into that subset of placemaking. Effectively to this day, you're more likely to search for the phrase 'creative placemaking' than just 'placemaking' according to research shared at Placemaking Week Europe. Even so, I visited Denmark's national center for design last year and learned their definition of creative placemaking was limited to the adaptive reuse of industrial space for creative industries. Hmmm...I would categorize that as adaptive reuse within the realm of the creative economy, but it is nowhere near encompassing what creative placemaking is about or why it's essential for society and public spaces. The Danish Design Center is not only teaching design for cities in Denmark, but is promoting their approach to leaders of cities and countries all over the world. We have to make sure we're visiting institutions and events promoting placemaking to ensure they're connected to the canon of knowledge that they're eagerly espousing. Graphic recording of the shared definition of placemaking at the 2023 Placemaking Week Europe conference. The Middle Road Forward: Balancing Education, Contribution and Innovation So, how do we define placemaking? Well, there are many shoulders to stand on, and a multitude of sources have contributed to our understanding. We have the insights of Jane Jacobs, the work of William H. Whyte and the Project for Public Spaces, the enlightening Social Life Project blogs, the empowering concept of the Right to the City, the global significance of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals and New Urban Agenda, Mike Lydon and Tony Garcia's illuminating book Tactical Urbanism, the equity frameworks championed by Mindy Fullilove, Majora Carter, and Blackspace, the refinements on architecture by Christopher Alexander and Jan Gehl, the community-building concepts of John McKnight and Peter Block, the health-oriented social infrastructure explored by Donald Appleyard and Erick Klinenberg, and countless other sources that have provided a solid foundation for our understanding. In fact, we've recently started compiling a list of books on placemaking for an American Placemaking Library and have already amassed over 100 titles spanning economics to urban planning, all of which contribute to the rich tapestry of ideas that shape the concept of place and placemaking. Our task is to ensure that we promote the "first principles" of placemaking and maintain an ongoing dialogue to evaluate and question what placemaking means, both on a global scale and within local contexts. As part of the PlacemakingUS network, we commit ourselves to learning and sharing the best and most useful knowledge we encounter with local practitioners throughout the country. We achieve this by engaging in visits, learning programs, and by actively participating in discussions wherever we're welcomed. We seek the support of our local partners, funders, and like-minded firms who share our belief in the wisdom of Jane Jacobs: "Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody." In an era where placemaking is at the forefront of urban development discussions, it is imperative that we do not leave its definition to chance. Failing to define placemaking, even to some degree, leaves it vulnerable to distortion and exploitation by those who may not have the best interests of our communities at heart. Let us remember that clarity in our understanding of placemaking is not just an intellectual exercise; it's a safeguard for the future well-being of our neighborhoods and cities. Op-ed by Ryan Smolar

Initiator, PlacemakingUS  In New York, urban street life outside your studio apartment is crucial. It’s a vital source of social connection. New to the city, I went for many walks with my dog, Arlow, and discovered that each block has a specific personality: maybe funky, stuffy or infuriating (hello, Time's Square). Neighborhoods are expressed in their architecture, the green spaces, the types of shops and eateries which draw an ever-changing flow of pedestrian traffic. Covid brought the additional element of outdoor dining to the mix. Existing and struggling restaurants expanded into the street with outdoor dining options. Not only did these structures occupy more space but offered an expansion of the public place. They changed urban street life and how we responded to our cityscape. This bond between people and place, called topophilia, is formed through human perception and experience when we are exposed to places. As I write to you today, I want you to examine your own experience with topophilia. Topophilia is not confined to a single city. So as you read, and then go about your day, I encourage you to take a more active role in fostering your connection with your city. Every city has its own charm. Your involvement can make a significant difference in creating a more vibrant and successful street life. According to Yi-Fu Tuan (geographer and writer who popularized Topophilia) a place is a physical area that encourages “stopping, resting and becoming involved.” When I walk through a sidewalk cafe, even though I have not ordered an appetizer or a drink, I interact, even in passing, with restaurant workers and diners. I create meaning in a more complex way for myself, as well as the patrons and servers. My fleeting presence contributes to the general atmosphere of the outdoor cafe or bar. Remaining open to spontaneous conversations with people enjoying their meals in outdoor dining spaces can not only deepen your connection with your community, but also with your street; insights into what makes these spaces unique to where you are. Outdoor dining has also left us with diverse temporary structures that need to be creative to maximize space and to be welcoming and attractive for patrons and passersby. (Passersby may be converted into patrons by having positive experiences with the outdoor structures, which is also economically beneficial for your community!). As you walk through your city, think about how people spend time in these semi-improvised buildings and move around and through them. Or is this a case of place versus space? Commuters, taxis drivers and delivery trucks complain that outdoor dining sheds took over spaces for parking and servicing the city, and replaced them with public places--perhaps only for the benefit of the restaurants. Congestion builds. Horns honk. Some outdoor dining structures are abandoned, decay and fall apart. How do we find the right balance? In ‘The Creative City: Foundations of the Creative City’, Landry calls public spaces in cities ‘neutral territory’ and considers how they generate creative ideas. He argues that places where people feel simultaneously comfortable, stimulated and challenged can be a great resource. These kinds of spaces generate creativity and change. Sidewalk cafes now offer New Yorkers more time in “key locations for the public realm.” New York streets become our collective third place, offering the widest range of serendipitous, and perhaps unpredictable, interactions between many different types of people. Sidewalks are now liminal spaces between establishments that are defined by brick walls and glass windows to their more visually and physically open structures. This is part of what makes us love New York, if you’re looking at the city as a placemaker that is. Where our ‘first place’ is our studio apartment, our ‘second place’ is our work, and now our ‘third place’ may be re-imagined to include an expanded version of our favorite eateries. But these may only be there for a moment. Sometimes these structures go up and are torn down within the blink of an eye. Post Covid, restaurants petitioned for open space infrastructure (see my previous article ‘Concrete to Cafes: The Evolution of Public Space in NYC’). Let the experience of Topophilia inspire you and let that enthusiasm circulate to those around you. Look for opportunities to be involved in signing petitions, or in writing letters of appreciation to city officials who played a role in your city’s open street program or in outdoor dining structures that you see make a positive impact. Jeff Siegler, author of ‘Your City is Sick’ comments, “Cities are not outcome oriented, but process-driven. Even when there is a clear consensus on what people want, there is truly no way to achieve it if we continue working through the current process a municipality has in place.” Allow your topophilia to change the way in which you appreciate and interact with your surroundings, granting it license to spark creativity and become a part of the process itself. Grab your camera or smartphone and head out to capture the essence of your town or city. Take pictures that showcase the unique character of different neighborhoods, the people, the architecture, the green spaces, and of course, the street dining experiences. Share these images on social media using a dedicated hashtag for your city, allowing others to appreciate the beauty and diversity of your urban environment. Embrace topophilia and let it inspire you to be an advocate for your community's thriving urban spaces.

|

AuthorsArticles contributed by placemaking experts across the US Archives

July 2024

Categories |

PlacemakingUS

|

PlacemakingUS Newsletters

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed