|

PlacemakingUS recently hosted the NYC Public Realm Roundtable at Pratt Institute School of Architecture with a halo of stars, including Mayor Adams' Office of the Public Realm, the incredible Department of Transportation (NYC DOT), leading firms in the cities-for-people space like Street Plans and Street Lab, and think-and-do tanks like the Design Trust for Public Space, Urban Design Forum and the Alliance for Public Space Leadership. It was an incredible event to be a part of and to organize from afar. To put it together, I spent a lot of time on the phone listening to New Yorkers kvetch about what's keeping their city from achieving the public realm greatness of international peers they highlighted, like Barcelona, Mexico City, Paris, and Montreal. And when it came down to it, by the 15th call, I was pretty surprised to be hearing the same lamentations I've gleaned from my own city, and towns across the country: our local permitting systems are squeezing the creativity, connectedness and joy out of American civic life. I know the story well from my own experience, long before I ever picked up the phone and dialed a 212 number. If you want to host a public space activation for your community, be prepared to fill out a ton of paperwork at a pre-determined time, get signatures from those affected by the "inconvenience," and pay a hefty fee before you're even assured that the permit will be issued. Once you receive your permit, you learn that this is a permit to get more permits. You might need a fire permit, a structural permit for a stage, a liquor permit, or a bunch of permits for individual food vendors. And don't get me started on insurance and three-compartment sinks! And while I get it—I understand why we, in principle, need some ways of permitting these activities and that there is liability and bad actors and abusers out there—it's truly long past time we recognize the amount of positive activities, programs, and stewardship we're denying in our public spaces every day by treating everybody like they're unauthorized actors needing to go through this rigmarole to support their local park, provide an economic platform for neighbors wanting to start businesses, or create additional playspaces for children and social spaces for us all. It was great learning about all the hard work being done in NYC to overturn this system, particularly the work of the Design Trust for Public Space. They recently completed a report called Neighborhood Commons: Reimagining Public Space Governance and Programming in Commercial Districts. The report's methodology brilliantly reminds me of the famed Chicago Sun-Times endeavor to open a fake bar called The Mirage Tavern in the 1970s. By actually going through the steps of trying to open the aptly named "Mirage" Tavern, the reporters and a watchdog group were able to meticulously illustrate the corrupt and flawed aspects of the procedures, which were riddled with shake-downs and graft. This isn't to say NYC's permitting process is run by Tammany Hall, but rather that the byzantine and inconsistent laws on the books and interdepartmental confusion create an impossible scenario for even trusted community-based organizations like Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) and Open Streets management organizations to maintain their noble efforts of creating, maintaining, and enlivening public space across the city. Another thorough exploration of these issues as they relate in particular to BIDs is presented in the Regional Plan Association's recent report entitled, GO LOCAL! Nurturing Neighborhoods & Advancing Equity, which postulates that "the City has an extraordinary opportunity to catalyze equitable public space investment in all neighborhoods by lifting constraints and actively affirming BIDs and other place-based partners in less-resourced areas." The author of the report, Tim Tompkins, who formerly ran the Times Square Alliance and is the Founding Director of Partnerships for Parks, is on a mission to say this goes beyond the BIDs to impacting all public space partners, from Friends of the Parks organizations to Community Boards. Now it's true: across the spectrum, the permitting process is not 100% impossible. We've encountered rare talented individuals who are permit masters. David Tamulonis, Events & Marketing Manager for the Erie Downtown Partnership, sits down one day a year with every department in his small city and gets hundreds of downtown activations permitted. He comes from a development background and is used to rigorous 18-month planning approaches and has adapted that to the lowly event permitting process. In Portland, Oregon, they've made great strides towards simplifying permitting and creating more categories of permits with easy web access to facilitate the process under the banner, Portland in the Streets. When I ran a BID in Santa Ana, California, our city's permitting process was a real clunker, requiring you to show up at City Hall and drop off paper documents and handwritten checks. My incredible operations manager, Jose Romo, went toe-to-toe with the City, crossing every 't' and dotting every 'i' such that the City eventually recognized the burden it was putting itself through and innovated to allow us to turn in one permit to cover up to six events, as well as simplifying and lowering the costs of pop-up vendors to a more equitable rate of $25/year for artisans and micro-retailers selling a few thousand dollars per year or less on our city streets. And though there are these rare bright spots, I think a former Mayor of Denver said it best when he lamented that "our challenge in government is to create an atmosphere where people don't have to use up their creativity fighting the system." Though well-resourced and employed experts are able to figure out the permitting systems, most citizens are left in the dark, and that results in a lack of their creativity and care hitting the streets in a meaningful way. The Better Block Foundation, a non-profit that specializes in turning underutilized public spaces into temporary demonstrations of vibrant areas, has dealt with dozens of permitting offices across the country. While they're quite adept and have honed their process to a 120-day start-to-finish approach, they encountered one city whose process was so overly complex that they hired a graphic artist to illustrate it. The resulting flowchart looked more complicated than the ones used to launch a SpaceX Super Heavy Rocket and demonstrates the need for cities to be aware of how they may be stifling lively, connected places in parks, plazas, commercial centers, and neighborhoods. On the phone with New Yorkers, I was both saddened and inspired when I was put in touch with Trey Jenkins, a BID leader in the Bronx in the 161st Street BID adjacent to Yankee Stadium. Without losing his upbeat positive attitude, Trey explained to me the challenges he was surmounting to provide public space amenities and proof of concepts to garner public-private investments to give the Bronx the type of public space pizzazz you might encounter in Manhattan or Brooklyn. "This is the greatest city in the world," Trey added, "let's make it happen." I heard a similar story from Tiera Mack, the Pitkin Avenue BID leader in Brownsville, Brooklyn. She wanted to create a small business opportunity and activate her public plaza, Zion Triangle, with a coffee cart, but a New York City Department of Parks & Recreation moratorium on concession agreements left the neighborhood uncaffeinated and the plaza underutilized. Beyond the BIDs, we were even more shocked to hear about the permitting woes of the neighborhood organizations partnering with the City to run hundreds of Open Streets across the cities. These pandemic-era programs have iterated year after year to provide unprecedented social space, play streets, outdoor dining, and biking and walking paths throughout the boroughs. We visited the legendary 26-block 34th Avenue Open Street and an emerging gem on 31st Avenue, along with the incredible commercial strip in Brooklyn along Vanderbilt Avenue managed by a dedicated group of neighbors. It was tearful to hear about the way these community-managed social spaces had brought whole communities together, kept businesses thriving, and provided critical space for well-being and activity. And yet, these Open Streets need to reapply for their permit every single month. They need to apply for special permits for certain types of activities the community wants to do, they have to maintain robust insurance policies, and rely on wide networks of volunteers without paid staff. Despite all these challenges, they persevere and even have a network where they can cry on each other's shoulders and vie for advice. An intriguing tale we encountered as we heard these stories was that of "The Hort," an equity-minded program of the Horticultural Society of New York that provides scaled services to these public space providers like the Open Streets and Plaza Programs across the City. The Hort gives one clue on how more services could scale up to support hundreds of public spaces across the City. Started as an entrepreneurial partnership between Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Horticultural Society of New York, The Hort began with a million dollars to provide those critical services that underpin these public spaces, including moving the barricades daily, landscaping, and maintenance. This program quickly proved its worth and has scaled to a $27 million NYC DOT contract, which underpins the success of most of the public-public partnership spaces we visited in areas outside of the uber-resourced Midtown Manhattan. This miracle at The Hort was lauded by all as a success and is a program that should be resourced, expanded, and brought to other cities. In addition, other platform services like insurance, gap funding, and even activities could follow a similar path. We were exposed to another public space platform at Street Lab, a design studio that has created a library of temporary furniture for public space activation that works with philanthropy, institutions, and the City to provide prototypical furniture to Open Streets in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens so they can begin to figure out the more long-term needs and wants of the community. Truly inspiring and incredible work from those rising to the occasion in our nation's most urban and densely-populated landscape. Through the action of the NYC Public Realm Roundtable, we heard the stories of individual actors experiencing pain points and red tape, where they should be invited as trusted partners to make great places for residents. We also learned these issues have been well-documented, and each of the plans mentioned above has a dozen recommendations put forth to streamline and enable positive action to move forward. Some of the participants in our roundtable, Jackson Chabot and Elana Ehrenberg, along with Rebecca Macklis of the Municipal Arts Society (MAS), even wrote an Op-Ed in May, Opinion: Free NYC’s Block Parties from Suffocating Red Tape, opining the same thing we're talking about here. So is there any hope?

There is a glimmer on the horizon. In May, Mayor Adams and the Small Business Services Division (SBS), which oversees 75 BIDs across the city, made an announcement aimed at addressing these issues. These include making $500,000 in grants available to offset insurance costs, launching a new "Trusted Partner" program to cut red tape for consistent partners delivering services and value to New York residents and visitors, and initiating a new pilot partnership with the Urban Design Forum. This partnership, called "Connected Corridors," will provide legal and logistical support to small BIDs like Trey’s and Tiera’s, who may have limited staff time to tackle giant recurring topics that can be better approached through a subject matter expert, third-party partner. We're writing about this topic so that it doesn't just get tackled in New York City but to present all cities and citizens with the opportunity to take stock of their permitting process and recognize the dead and dangerous spaces that pervade our cities. These spaces could be co-activated by citizens through easier and less expensive processes. We got the good news that the Design Trust for Public Space has received funds to continue their work and continue to present their materials to the New York City Law Department, where they feel legal language and liability aversion are where the rubber needs to meet the road. If there are cities out there, philanthropies, political action groups, or even economically-minded groups who see the potential of public space as a platform for the regeneration of our places and our economy, we hope you will get in touch and we can mutually support this body of work and this changing of the guard from one-size-fits-none to loosening the levers for many more to utilize public space for cultural activities, social gatherings, micro and mobile businesses, and health and well-being. The other option is to watch as our public spaces continue to wither under bureaucratic constraints. It's time to break free and let our cities flourish with creativity and community spirit. Story by Ryan Smolar Photos by Ryan Smolar, TJ Maguire and Ethan Kent

0 Comments

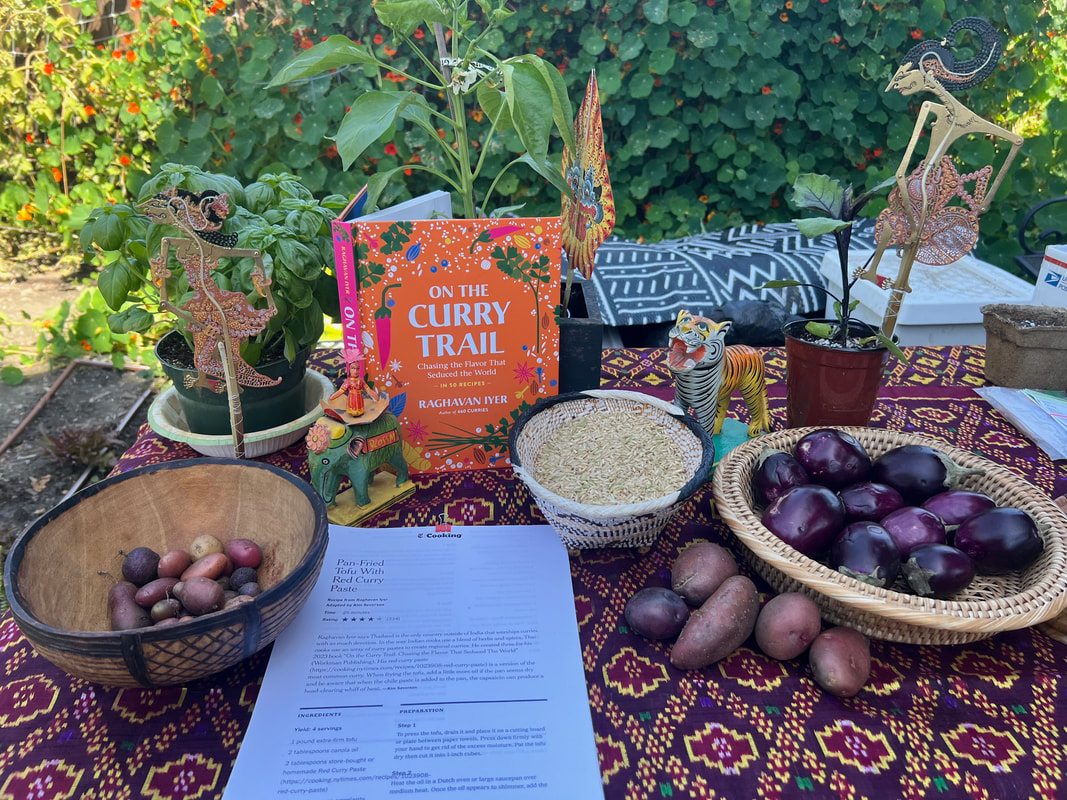

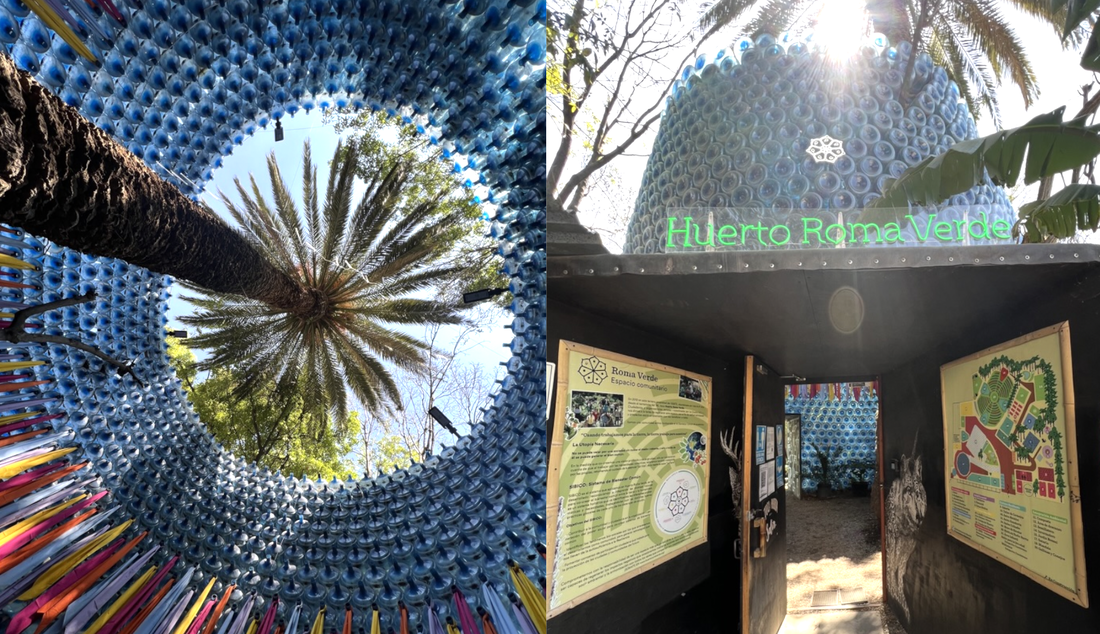

This three-day event brought together local placemakers in the Long Beach, California area to examine our food system and how the community is coming together to grow, share, and sell food with one another. Non-profit sponsor and organizer Long Beach Fresh also refers to this as a convening of seeders, feeders, and eaters. Ultimately, this gathering celebrates how, through nourishing ourselves and others through healthy food, we can create more robust, more equitable communities. This summit was also grounded in the theories of the placemaking movement: that we all have a collective responsibility to reshape our environments in ways that serve the holistic needs of all, and that can be accomplished through education, organizing local leaders, access to resources and empowerment to all people living in our locales. I began my day on Friday in an industrial area of Long Beach at the Foodbank of Southern California. For the last 47 years, this non-profit center has worked out of this warehouse to distribute food with over 700 non-profit partners. I was a guest at an opportunity luncheon, where local Southern California farmers, food policy experts, non-profit leaders, and government workers came together to learn about the future partnership opportunities that were coming up to help strengthen the infrastructure of the local food network. We enjoyed a delicious farm-to-table lunch from a local chef while seeing the designs for the renovation of an additional distribution hub, innovative vehicles built for better food drop-off in small urban streets while also engaging in networking and discourse about how to shift food bank food away from the traditional reliance on canned and processed food into healthier offerings through partnerships with local farmers. Next, I met students, food policy experts, funders and grassroots leaders for another discussion in the beautiful setting of Moonwater Farm in the nearby city of Compton. Here we marveled at what is possible when one uses permaculture techniques, as Professor Kathleen Blakistone from the Department of Plant Science at Cal Poly Pomona has transformed the urban property into a wonderland that includes not only chickens, vegetable, herb, and fabric dyeing gardens but also ultra-friendly Angora goats. We heard about the state of funding for local food programs and non-profits since COVID-19 from Melanie Wong from the Food Policy Council. Long Beach Fresh's Ryan Smolar shared his inspiring vision for a more integrated, robust, financially secure food system for all through public-private partnerships and the strengthening of local non-profit leaders. That evening, during the Bixby Knolls art walk, I visited the Long Beach County Fair. I watched a dance video featuring special needs students in the farming education program at Sowing Seeds for Change, promoting healthy food in local convenience stores. A photography project I shot of the six convenience stores participating in the Farm 2 Market program was displayed on the wall, highlighting the immigrant owners of the businesses who dared to innovate by selling produce alongside their traditional fare from local farms. There was a blue ribbon contest awarding the best produce and cottage foods produced locally, a creative station for kids, flower wreaths, freeze-dried fruits, and plants for sale, all amidst the blue grass honky tonk. Saturday morning began at the Growing Experience Farm in North Long Beach, where I watched my first ever Crop Swap: an amazing exchange of backyard produce that attracted plentiful food from growers all across the city. One of my favorite items was the candied lemon peels that one resident brought to share. Chef Dina Feldman of Feel Good Salsa demonstrated how to make a healthy vegetable salad, and I took home a couple of containers to share. I learned how residents promoted the idea of bringing aspects of Blue Zones to the local Long Beach community to enhance longevity by promoting healthy food, physical activity, and community connection. A walk topped off this visit through the beautiful six-acre space, which not only includes a teaching garden and vertical gardens, but also an aquaponics system which grow food and fish in a closed-loop system. The day's second stop was at Zaferia Garden, part of the Long Beach Organic community gardens network. This land was filled with growing plots where a railroad line once ran, and on this day, a young boy greeted me with an offer of fresh-squeezed lemonade. His father was hand-turning wooden dibbers, which help expand the opportunity for everyone to participate in the planting process despite physical limitations while encouraging soil health. Live jazz music filled the air, and many starter plants were for sale to support the non-profit: I bought a strawberry plant, some basil, and lettuce to plant at my Long Beach home. In this setting, I heard talks from the City of Long Beach's Environmental Services Bureau about food waste prevention and food recovery processes from non-profit Food Finders. I downloaded the FoodKeeper app for my iPhone to educate myself on better food store maximization. The last stop was at the kick-off of the painting of a beautiful food mural on the side of the Southeastern Asian grocery store A&F Market, one of the participants in the Produce 2 Market program I mentioned earlier, part of the City of Long Beach Department of Health and Human Services through the utilization of funds from the Long Beach Recovery Act. I met local community artists at this site, including Amy Tanaka and our local United Way representatives. I learned about their organization's shift back to a community chest model, focusing on investing in local grassroots community groups that have their feet on the ground so that community needs are met successfully through partnerships with neighborhood leaders. Sunday afternoon was the last day of the summit, and it consisted of a meeting for a Vegetarian Cooking demonstration in the learning and teaching garden of the Long Beach Master Gardener's program behind Casa Chaski's Peruvian Restaurant. Louisa Bonnie cooked Thai red curry with vegetables while community members shared ideas about documentary film projects and seed and plant shares. I met Master Gardener Lee White, who tends the beautiful space. Last but certainly not least, I took a herbalism walk with renowned herbalist teacher Julie James in the beautiful Willow Springs Park near Signal Hill. I learned about many traditional nutritional and medicinal uses of the local flora and fauna, along with the history of the space from the Friends of Willow Springs Park. I was surprised to learn that in the 1920s, Long Beach had planned to turn the park into a community center, similar to San Diego's Balboa Park. However, someone discovered oil, and the space instead came to host 70 wells pumping day and night. Yet today, many of those pumps are no longer active, and the local landscape is returning to what it once was. This beautiful spring day was full of yellow lilies, and I strolled down the walking trail alongside a mural celebrating the wisdom and connection to the land of the indigenous Tongva people. Just earlier in the day, I had dropped off food scraps at Farm 59 (also in that space) to Long Beach Compost while picking up free processed compost and mulch to prepare the soil at my home to begin my own participation and journey into the seemingly magical world of growing life from the soil. This weekend was both educational and thought-provoking. It made me reflect on the vision of what I would like my neighborhood to look like: full of food forests alongside walking trails where I can meet neighbors, easily accessible, affordable, healthy local food, and warm shelter for all who live beside me, as well as the opportunity for all to share their gifts in the beautiful community we are cocreating here in Long Beach. I met many others this weekend who share the same vision and desire to partner to manifest this New Renaissance along with our Mother Earth: reimaging a world, an urban city where all can flourish, be nourished, live integrally within our natural environment, and shape our built environment into creating spaces where people can join in on this movement and reimagine how we live. Isn't this what placemaking is all about? Bringing together creative, visionary, and rooted community members to shift energy and stir up the pot of complacency and the status quo to reshape the world we have been born into, one we only dream of living in but also can envision passing along to those who will come after us? We are responsible for honoring our vision and desires for peace and prosperity for all while respecting the indigenous wisdom still in this land and learning from nature how to live in this time in history to promote social change and hold dear to the near future where love shows the way.

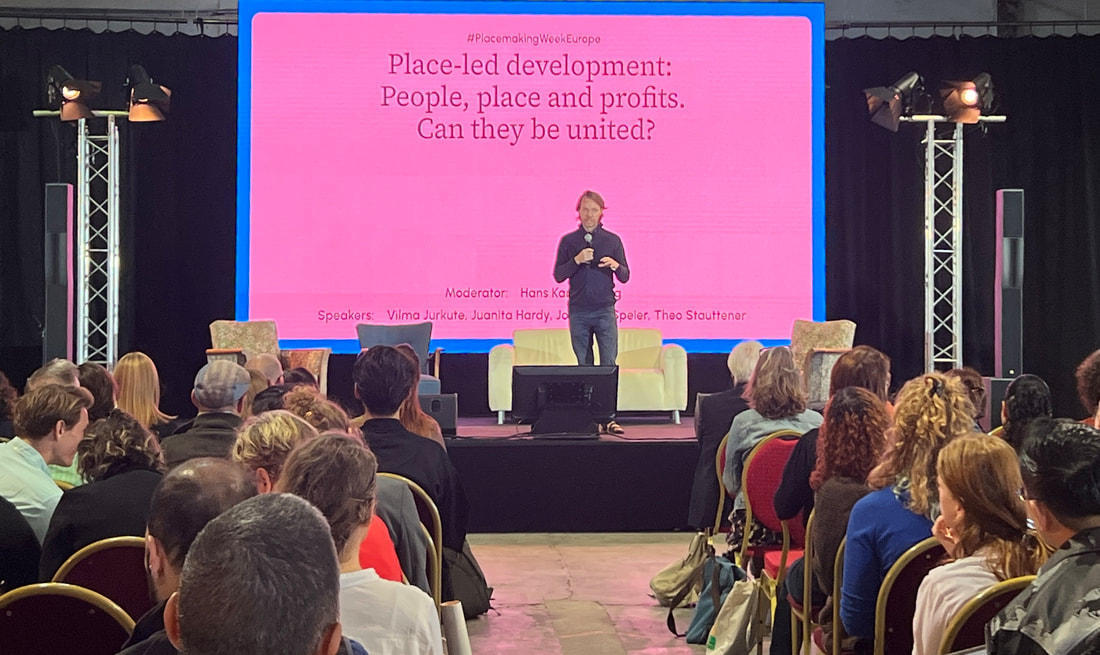

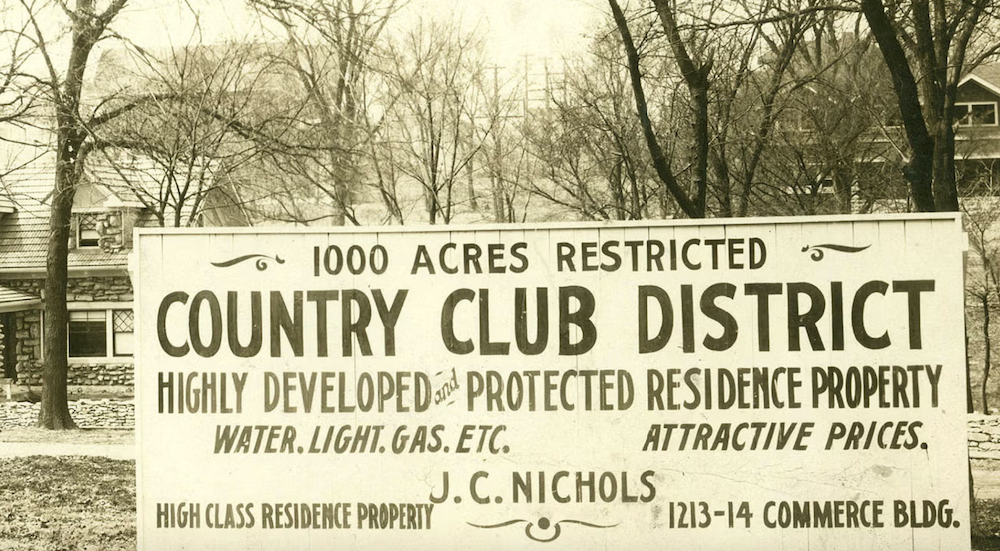

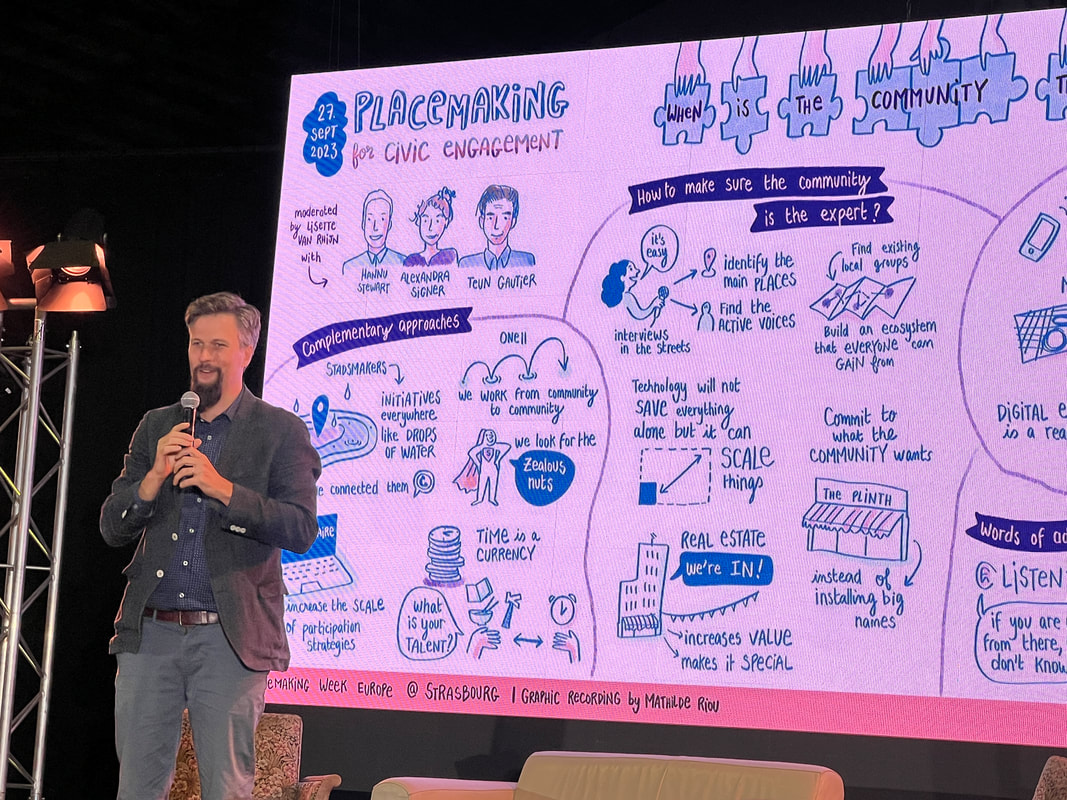

Community gardens, urban farms, and public edible landscapes infuse fresh food into our city lives, grounding us in the natural world and its seasonal rhythms. However, these spaces often come with barriers: big fences, locked gates, and a sense of exclusivity that can make nearby residents scoff, “Community garden? Not for me.” But inside, there’s a different story. Those who tend the plots are often deeply connected to the neighborhood, though a clear divide exists between them and those left outside. We see placemaking as a game-changer in the world of urban agriculture and community gardening. It’s about breaking down barriers and welcoming more people in, especially in low-food-access neighborhoods where a garden could revolutionize local health and social safety nets. Transforming Spaces: Tips for Urban Ag Sites1. Rethinking Boundaries: The Art of Fencing Yes, gardens indeed need fences—to shield them from hungry animals that could ravage a garden overnight and to deter the occasional vandal or uninvited gleaner. Yet, some fences we see are so imposing they seem to scream "food maximum security" rather than "food security." Here's how we can turn barriers into welcoming features: Embrace Living Fences: Cultivate a fence with a purpose. Planting blackberries or other vine crops can transform a stark fence into a lush, living boundary. It becomes a beautiful hint of the bounty inside and extends an open invitation for passersby to enjoy a summer berry and perhaps, strike up a conversation with the gardeners. Strategic Setback: Sometimes, it's not just what you plant but where you place it. Many gardens push their fences to the very edge to maximize space. However, setting the fence back even just a bit can create a welcoming 'front yard' effect. This space can serve as a mini public square, offering benches, a spot for food sharing, or a communal herb garden with mint or rosemary for anyone to harvest. By reimagining how we delineate our garden spaces, we can foster a sense of openness and community while still protecting the fruits of our labor. Try setting the fence back. It’s a simple trick that creates a welcoming front yard vibe, offering space for food sharing, seating, or public herb gardens. 2. Crafting the Welcome Artful Entrances: The entrance should be a testament to the garden's ethos, inviting curiosity and interaction. An attractive sign or archway that captures the essence of the garden can intrigue and draw in visitors, setting the tone for the experience within. Informative Displays: Clarity invites participation. A well-designed welcome area should offer essential information at a glance – opening hours, contact details, and upcoming events. This openness not only encourages community involvement but also integrates the garden into the rhythm of neighborhood life. Neighborhood Signage and Wayfinding: Effective wayfinding ensures that the garden is a community fixture, not a hidden secret. Signs placed throughout the neighborhood can guide residents and visitors to this verdant haven, making it an accessible destination for all. Consider maps, directional arrows, and even digital markers for those using smartphones to navigate. 3. Programming and Open House: Cultivating Community Through Activity Urban gardens are more than plots of land for cultivation; they are vibrant community centers that offer a remedy to the mental health crises and isolation prevalent in today's society. To truly flourish, these spaces must provide a variety of reasons for people to gather, connect, and engage beyond the care of their garden beds. Wellness and Recreation: Activities like yoga, including popular variations such as goat yoga, invite people to unwind and connect in the serenity of nature. These sessions offer a dual benefit: promoting physical health and creating a communal rhythm that resonates through the garden. Direct Engagement with Nature: Initiatives like 'U-Pick' events and farm stands do more than just provide fresh produce; they invite hands-on interaction with the garden's bounty. This direct engagement is a tangible way for community members to support the garden's sustainability while enjoying the fruits of their labor. Community Exchanges: Our 'Crop Swap' program is a testament to the power of sharing. Over eight years, participants have exchanged over 14 tons of produce, seeds, and gardening insights, fostering a rich tapestry of communal knowledge and culinary diversity. Open Hours and Amenities: By opening the garden for regular visiting hours, offering volunteer opportunities, or simply providing a space where one can work remotely with the added benefit of free Wi-Fi and garden-grown herbal tea. Mixing uses by adding a mobile book shops or flower store, can transform these green spaces into hubs of community life. In essence, gardens are not just about cultivating food; they're about cultivating community. PlacemakingUS recognizes the profound potential that lies in each urban agriculture site. Through our dedicated efforts, we visit and assist gardens in realizing their fullest capabilities, transforming them into vibrant, communal spaces that extend far beyond the confines of cultivation. We are committed to collaborating with local food communities, bringing the wisdom and practices of placemaking to these essential urban spaces. Our work is more than a passion—it's a critical step toward a more sustainable society. By enhancing these gardens, we contribute to carbon sequestration, reduce food miles, and strengthen the fabric of our communities, creating spaces of social cohesion and comfort. Aligning with the universal principles for sustainable development advocated by UN-Habitat, we believe in nurturing spaces that foster a deeper connection to our environment and each other. We invite you to join us in this transformative journey, reshaping our urban landscapes into thriving, sustainable, and inclusive communities. Article and Photos by Ryan Smolar, Co-Director, PlacemakingUS Placemaking, a term with noble intentions in the realm of urban development and community-building, is at risk of losing its true essence. As we grapple with the ambiguity surrounding this concept, there is a pressing need to define placemaking and defend it. Without a clear definition or underpinning principles, the term becomes vulnerable to distortion, manipulation, and misappropriation by commercial and political entities and the uninformed. In this article, we delve into the critical importance of upholding what we mean by the word, 'placemaking' and the consequences of allowing the term to be used willy-nilly. A Most Meaningless Word Recently, an article in Dezeen created ripples within our placemaking community with its deliberately provocative headline: "I have a confession to make: I have no idea what placemaking is." The piece aimed to make a stir and ignite debate, cited the ambiguous language often used to describe the multi-faceted subject by quoting at length from Project for Public Space's lofty explanations of the concept. Unfortunately, the fine-buttered words and finessed phrases from their website do seem to paint placemaking as a panacea that sounds suspiciously like the snake oil salesman's remedy for cities. In response to the grenade Dezeen threw into the room, the co-director of Placemaking Europe penned a response entitled, "I have a confession to make: I don’t care what placemaking exactly is." His article argues that delving into semantics is a futile endeavor when placemaking appears to be an overarching term encompassing individual, positive actions aimed at enhancing our urban spaces. While, in my heart, I'm inclined to agree, this philosophical stance raises concerns—especially for a group that recently brought together 500 placemaking practitioners and eager learners, providing them with content that sought to define placemaking through speeches and interactive workshops. A precarious panel on placemaking at Placemaking Week Europe 2023 in Strausborg, France. The Dangers of (Mis)Defining Placemaking At the Placemaking Week Europe event last month, I found myself stunned at what was being described as placemaking from their main stage. During a talk entitled, Place-Led Development - People, place, and profits. Can they be united? an elderly woman of color named Juanita Hardy, who is the Senior Visiting Fellow for Creative Placemaking for Urban Land Institute, had this to say: "Placemaking started in the United States in the 1920s when a developer in Kansas City built a successful shopping mall 4 miles from the downtown heart." Besides what sounds obviously wrong with that statement, I knew as one of the few Americans in the room who's been to Kansas City several times that she was referring to County Club Plaza and its creator, JC Nichols. While Country Club Plaza is a charming piece of faux urbanism with a mix of automobile access, walkability, and even great programming, this project is more notably the development where suburban racial segregation took root in America. A recent article in Slate called, "The Made Who Made the Suburbs White" more accurately describes the Country Club District, not for its placemaking principles but for its pioneering of the use of racial covenants: not allowing minorities to rent or buy in the district. The Country Club's "protected" district was a progenitor of the racially-segregated suburbs. Photo courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri To quote the Slate article at length: "In the 1930s, the Nichols Way received a boost from the federal government...To Kevin Fox Gotham, a professor of sociology at Tulane University and author of Race, Real Estate, and Uneven Development, it seemed as if the Federal Housing Authority had “adopted [Nichols’] methods and practices almost verbatim.” This means there is a strong connection between the racial covenants that JC Nichols pioneered with the federal practice known as redlining, which segregated and destroyed black neighborhoods across the country. JC Nichols should be remembered as the father of racial strife, white flight, and our national inequities, but not the father of placemaking without the caveats that we now have federal laws like the Community Reinvestment Act and Fair Housing Act to protect people who look like Juanita and me against the ideas and actions of men like him. The Line is a futuristic, 'sustainable' megacity project in Saudi Arabia that aims to create a 170-kilometer-long, car-free urban development in the desert. The project has produced a mini-series calling the architects, planners and futurists associated with the plop project as "The Line's Placemakers." Letting Commercial Interests and Professionals Define Placemaking In 2021, PlacemakingUS was approached by Ph.D.'s at the research department of a global architecture firm asking us to endorse a report they made to educate their 1,000 employees on "The Subtle Art of Placemaking." But after reading it, I had to write them a pointed rebuke that their report should rather be called "The Subtle Art of Placebaking," i.e. taking the ingredients of placemaking and utilizing them in a measured, professional and controlled way to bake a pre-packaged "place cake." Notably because their guide lacked any mention of co-design or community participation, failed to explore the use of the temporary to inform permanent solutions, neglected discussions of sustainability and equity, and omitted fundamental concepts like the mixing of uses. Another group, the International Downtown Association (IDA), has recently become an accrediting organization. They have introduced the suffix "LPM" to designate "Leadership in Place Management" to those bold enough to pass a 100-question multiple choice test. One of the core domains of knowledge for this accreditation is about placemaking expertise. While the information promoted by IDA maintains high quality and is crowd-sourced, it is primarily driven by the commercial interests of individuals representing business and property owners. I've encountered numerous business improvement districts (BIDS) whose idea of placemaking is constructing outdoor ice skating rinks in arid and subtropical regions of the United States. While these novel gimmicks inject fun and vitality into cities, they often disregard the fundamental principles of sustainability, including water use, energy consumption, non-renewable materials, and transportation costs on the environment. These projects reveal the trend that BID placemakers are often just re-branded marketing/events staff whose motivations are to follow trends and attract customers, rather than to ensure that the city remains accessible for everyone to contribute creatively. Kady Yellow, a distinguished practitioner, bucks this trend by demonstrating that a BID-embedded placemaker can serve as a powerful catalyst for driving systemic change and amplifying diverse voices. Through her roles as the Director of Creative Placemaking in both Flint, Michigan, and Jacksonville, Florida, she has illuminated the transformative potential of resident-led placemaking programs within business districts. Her initiatives not only educate the community about their role as placemakers but also provide essential funding and leverage the BID's unique privileges, granting access to permits, spaces, and relationships for collaborative city-building. Similarly, Richard Amore at the Vermont State Department of Commerce worked with his state legislature to create crowd-matched funds to make community-led and supported placemaking initiatives more accessible through the a 2:1 match of local funds raised for their own ideas to make their communities into Better Places. A business improvement district building a temporary, outdoor ice skating rink in sunny Southern California as a "placemaking" project. This wood was cut just for the project, but boosters say it will be re-used for 5 winters. To Define AND Defend Ethan Kent, leader of our PlacemakingX global networks, often upholds the ooey-gooey consistency of the made-up word placemaking saying there's great power in letting people define placemaking for themselves and the plasticity of the definition lends to the field's necessary adaptability. As an idealist, I agree, but the realist side of me recognizes that as we let placemaking blow in the wind, other interests are defining it and giving it a bad name such that many low-status communities now prefer the term placekeeping, that is keeping the so-called placemakers away so that the neighborhood can continue to exist without cultural and physical displacement. This issue takes many forms, as even our sister network, Placemaking Collective UK, is considering changing their name to be called the Place Collective UK, due to the perceived 'wonkiness' of our term. They were advised to keep placemaking in their name, yet another network, Peacemakers Pakistan, has struck a unique balance by alluding to placemaking while adapting their name to the most relevant challenges and opportunities of their context. A good example of the need to define and defend placemaking can be illustrated by the National Endowment for the Arts-funded white paper "Creative Placemaking" published by Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa in 2010, which set the stage: "In creative placemaking, partners from public, private, non-profit, and community sectors strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood, town, city, or region around arts and cultural activities. Creative placemaking animates public and private spaces, rejuvenates structures and streetscapes, improves local business viability and public safety, and brings diverse people together to celebrate, inspire, and be inspired." This report, which has been cited nearly 700 times in further works, helped define that field and resulted in over a hundred million dollars of investment into that subset of placemaking. Effectively to this day, you're more likely to search for the phrase 'creative placemaking' than just 'placemaking' according to research shared at Placemaking Week Europe. Even so, I visited Denmark's national center for design last year and learned their definition of creative placemaking was limited to the adaptive reuse of industrial space for creative industries. Hmmm...I would categorize that as adaptive reuse within the realm of the creative economy, but it is nowhere near encompassing what creative placemaking is about or why it's essential for society and public spaces. The Danish Design Center is not only teaching design for cities in Denmark, but is promoting their approach to leaders of cities and countries all over the world. We have to make sure we're visiting institutions and events promoting placemaking to ensure they're connected to the canon of knowledge that they're eagerly espousing. Graphic recording of the shared definition of placemaking at the 2023 Placemaking Week Europe conference. The Middle Road Forward: Balancing Education, Contribution and Innovation So, how do we define placemaking? Well, there are many shoulders to stand on, and a multitude of sources have contributed to our understanding. We have the insights of Jane Jacobs, the work of William H. Whyte and the Project for Public Spaces, the enlightening Social Life Project blogs, the empowering concept of the Right to the City, the global significance of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals and New Urban Agenda, Mike Lydon and Tony Garcia's illuminating book Tactical Urbanism, the equity frameworks championed by Mindy Fullilove, Majora Carter, and Blackspace, the refinements on architecture by Christopher Alexander and Jan Gehl, the community-building concepts of John McKnight and Peter Block, the health-oriented social infrastructure explored by Donald Appleyard and Erick Klinenberg, and countless other sources that have provided a solid foundation for our understanding. In fact, we've recently started compiling a list of books on placemaking for an American Placemaking Library and have already amassed over 100 titles spanning economics to urban planning, all of which contribute to the rich tapestry of ideas that shape the concept of place and placemaking. Our task is to ensure that we promote the "first principles" of placemaking and maintain an ongoing dialogue to evaluate and question what placemaking means, both on a global scale and within local contexts. As part of the PlacemakingUS network, we commit ourselves to learning and sharing the best and most useful knowledge we encounter with local practitioners throughout the country. We achieve this by engaging in visits, learning programs, and by actively participating in discussions wherever we're welcomed. We seek the support of our local partners, funders, and like-minded firms who share our belief in the wisdom of Jane Jacobs: "Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody." In an era where placemaking is at the forefront of urban development discussions, it is imperative that we do not leave its definition to chance. Failing to define placemaking, even to some degree, leaves it vulnerable to distortion and exploitation by those who may not have the best interests of our communities at heart. Let us remember that clarity in our understanding of placemaking is not just an intellectual exercise; it's a safeguard for the future well-being of our neighborhoods and cities. Op-ed by Ryan Smolar

Initiator, PlacemakingUS  In New York, urban street life outside your studio apartment is crucial. It’s a vital source of social connection. New to the city, I went for many walks with my dog, Arlow, and discovered that each block has a specific personality: maybe funky, stuffy or infuriating (hello, Time's Square). Neighborhoods are expressed in their architecture, the green spaces, the types of shops and eateries which draw an ever-changing flow of pedestrian traffic. Covid brought the additional element of outdoor dining to the mix. Existing and struggling restaurants expanded into the street with outdoor dining options. Not only did these structures occupy more space but offered an expansion of the public place. They changed urban street life and how we responded to our cityscape. This bond between people and place, called topophilia, is formed through human perception and experience when we are exposed to places. As I write to you today, I want you to examine your own experience with topophilia. Topophilia is not confined to a single city. So as you read, and then go about your day, I encourage you to take a more active role in fostering your connection with your city. Every city has its own charm. Your involvement can make a significant difference in creating a more vibrant and successful street life. According to Yi-Fu Tuan (geographer and writer who popularized Topophilia) a place is a physical area that encourages “stopping, resting and becoming involved.” When I walk through a sidewalk cafe, even though I have not ordered an appetizer or a drink, I interact, even in passing, with restaurant workers and diners. I create meaning in a more complex way for myself, as well as the patrons and servers. My fleeting presence contributes to the general atmosphere of the outdoor cafe or bar. Remaining open to spontaneous conversations with people enjoying their meals in outdoor dining spaces can not only deepen your connection with your community, but also with your street; insights into what makes these spaces unique to where you are. Outdoor dining has also left us with diverse temporary structures that need to be creative to maximize space and to be welcoming and attractive for patrons and passersby. (Passersby may be converted into patrons by having positive experiences with the outdoor structures, which is also economically beneficial for your community!). As you walk through your city, think about how people spend time in these semi-improvised buildings and move around and through them. Or is this a case of place versus space? Commuters, taxis drivers and delivery trucks complain that outdoor dining sheds took over spaces for parking and servicing the city, and replaced them with public places--perhaps only for the benefit of the restaurants. Congestion builds. Horns honk. Some outdoor dining structures are abandoned, decay and fall apart. How do we find the right balance? In ‘The Creative City: Foundations of the Creative City’, Landry calls public spaces in cities ‘neutral territory’ and considers how they generate creative ideas. He argues that places where people feel simultaneously comfortable, stimulated and challenged can be a great resource. These kinds of spaces generate creativity and change. Sidewalk cafes now offer New Yorkers more time in “key locations for the public realm.” New York streets become our collective third place, offering the widest range of serendipitous, and perhaps unpredictable, interactions between many different types of people. Sidewalks are now liminal spaces between establishments that are defined by brick walls and glass windows to their more visually and physically open structures. This is part of what makes us love New York, if you’re looking at the city as a placemaker that is. Where our ‘first place’ is our studio apartment, our ‘second place’ is our work, and now our ‘third place’ may be re-imagined to include an expanded version of our favorite eateries. But these may only be there for a moment. Sometimes these structures go up and are torn down within the blink of an eye. Post Covid, restaurants petitioned for open space infrastructure (see my previous article ‘Concrete to Cafes: The Evolution of Public Space in NYC’). Let the experience of Topophilia inspire you and let that enthusiasm circulate to those around you. Look for opportunities to be involved in signing petitions, or in writing letters of appreciation to city officials who played a role in your city’s open street program or in outdoor dining structures that you see make a positive impact. Jeff Siegler, author of ‘Your City is Sick’ comments, “Cities are not outcome oriented, but process-driven. Even when there is a clear consensus on what people want, there is truly no way to achieve it if we continue working through the current process a municipality has in place.” Allow your topophilia to change the way in which you appreciate and interact with your surroundings, granting it license to spark creativity and become a part of the process itself. Grab your camera or smartphone and head out to capture the essence of your town or city. Take pictures that showcase the unique character of different neighborhoods, the people, the architecture, the green spaces, and of course, the street dining experiences. Share these images on social media using a dedicated hashtag for your city, allowing others to appreciate the beauty and diversity of your urban environment. Embrace topophilia and let it inspire you to be an advocate for your community's thriving urban spaces.

Before COVID, New York City restaurants, often long and narrow, would occupy the base of a tenement building, their designs leaning into the cozy or crowded nature of an evening dining out in New York. When COVID restrictions began, a restaurant which could typically accommodate 40 diners, now had its occupancy dramatically cut down to 10. A saving grace for many; outdoor dining structures, would expand into lanes of traffic, allowing for an additional 16-20 patrons, depending on the size of their business frontage. This successfully spread people out, however now they were exposed to the busy street life, with traffic on one side and pedestrians on the other. We know that this change was made to prioritize safety during this public health crisis, but how would restaurants adapt long term? They would need to be creative to extend their ambiance out of their interior space, and incorporate their dynamic neighborhood around them. How would this change the nature of public space when it comes to outdoor dining structures? Something we’ll touch on in later blogs is the potential for a “greening” of New York City. I’d argue sidewalk cafes are an important first step here. When you approach an outdoor dining structure, perhaps you’re considering the durability, how protected you’ll be from the traffic or weather. But if you appreciate art and design you might also be considering its artistic contribution to the city. I encourage you to really take them in when in passing, or while dining. Consider their unique design, function, connection to their surrounding community. But we have to keep in mind that the outdoor dining structures we are enjoying today in 2023, have been rapidly developed from the first iteration in 2020. With the need well established, tactical urbanism took place to start them off, that being; low-cost, temporary interventions that really quickly transformed the public space of our streets and sidewalks. In July 2020, NYC released guidelines for expanding dining onto the streets - ‘NYC sidewalk cafes’. The pandemic in this context really exemplified how the use of space is constantly evolving. The goal of NY’s Open Restaurant program is; “an effort to implement a citywide multi-phase program to expand outdoor seating options for food establishments to promote open space, enhance social distancing, and help them rebound in these difficult economic times.” - DOT, N. Y. C. Restaurants had two options here: individual establishments could apply and use their sidewalk or curb lane adjacent to their business, or they could become part of an open street. An open street is a temporary full closure that beautifully has to be community based. A group of three or more restaurants on a single block can apply to temporarily close traffic all together. It’s an interesting time now in 2023, where we can see the sidewalk cafes and their impact on the urban landscape with some hindsight and perspective. The success of outdoor dining encouraged the city to create more permanent structures. Some questions to ask in evaluating the wide range of outdoor dining include: How durable are their wind barriers, their carpentry, heaters for the colder months or even choice of lighting? For many establishments across Manhattan, you can perceive the permanence of their structures upon first glance. Sidewalk cafes were first built in quick and effective ways to define a space. Looking to space out diners over 6 feet apart, while allowing ADA* access, quick constructions could take many forms. Most using construction palettes, tent like structures, and repurposed hardware. The diner's proximity to cars raised an important design question; how to ensure safety for diners while aesthetically aligning with its corresponding restaurant. As this design question was asked, designers and artists answered. Overcoming obstacles of function, resulted in creative design, public art and ultimately placemaking through the creation of these structures. The first iterations of sidewalk cafes were defined by function, but have since evolved and will continue to, thanks to artists, designers and placemakers. Sidewalk cafes as a whole have changed the way in which New Yorkers operate within their city. In such a pedestrian friendly city like New York we can see how important thoughtful public space design can be. However, the balance between creating these spaces, as placemakers ourselves, while maintaining the necessary processes that are required within the urban landscape will require innovation and collaboration. Something that excites me as I consider the possibilities for creative problem solving. How can we use this as a jumping off point to demonstrate the potential for greening cities and reorganizing the space we currently have? The unique circumstances around the emergence of sidewalk dining in NY created conditions where new interventions were being made bringing placemaking even further into the forefront of the conversation when we look at the future of our cities.

So many of Southern California’s city and suburban parks boast picturesque views, yet their poor access, amenities and vast underutilization perpetuates a peculiar paradox. Only a week after spending an eye opening Placemaking Weekend in New York City, the stark contrast related to parks in my California city have become painfully evident to me. While many people understand, especially due to COVID, that within dense urban spaces, public parks are vital life-giving contributions. The understanding that parks contribute not only to the well-being and quality of life, but also to mental health is important. Parks offer a connection with nature, overcoming social isolation, acceptance toward building social life in public spaces as was well described in the New York Times article Where We Are by Pierre-Antoine Louis. However, in California the regular issue of inequality in access, amenities and underutilization in public city parks is really shocking. The issue is widely exacerbated by my state’s grossly over developed infrastructure that continues to perpetuate car culture as its god. In the land of never-ending highways and traffic snarls, the very idea of strolling to a city park in many California cities instead seems like a whimsical fantasy. California's car culture continues to reign supreme, its roads crafted with an audacious ambition that defies reason. Pedestrians and “utility cyclists” or what are known as “commuter cyclists” are harshly judged in California as mere socio-economically challenged side characters in California’s theatrical production of public space access, many of which are unhoused. Those in low-status communities are regularly forced to navigate labyrinthine streets, with no crosswalks, that prioritize the almighty automobile. Moreover, many of these communities have high statistical deaths related to walking and bike riding. California's car-oriented infrastructure exacerbates the problem of inequitable access to parks. As demonstrated in the television series "Portlandia," which humorously critiques California's traffic culture, the dominance of car-centric planning and infrastructure creates barriers to accessing parks for communities relying on public transportation or active modes of transport. This perpetuates social isolation and restricts opportunities not only for marginalized but all communities to engage with nature and enjoy the benefits of green spaces. Now contrast this to pedestrian rich, walkable New York City, where parks beckon from every corner, inviting residents of all races, classes and visitors alike to partake in the vibrant tapestry of urban life. In the land of sunshine, palm trees and beaches one would expect an abundance of parks accessible to all. Yet, the reality is more akin to a twisted game of hide-and-seek. California seems to have a knack for segregating parks along racial lines. It's as if the trees and grass themselves hold a membership card. While affluent neighborhoods in California flaunt their green spaces like status symbols, low-status communities are left longing for more public parks, its nature as respite from overcrowded and impacted neighborhoods and basically a breath of fresh air. It's as if the powers-that-be have declared amenity rich parks a privilege reserved only for the chosen few, leaving the rest of us to wander aimlessly through hot, sun soaked sprawling concrete deserts. It seems to be the wisdom of City Parks and Recreation, that “Parks are for no one." Why bother with vibrant, lively parks filled with people enjoying nature and engaging in recreational activities when we can have empty, desolate spaces that serve as a testament to our commitment to solitude and social isolation? In Orange County some examples include: Fullerton's Gillman Park described on reddit as one of the most underutilized parks in the city. Another is Frontier Park in the city of Tustin which even designates it as "not busy" online. Yes, California cities are littered with these kinds of green spaces, forget about the concept of community and social interaction. Who needs that when we can implement defensive design strategies to deter people from actually using the parks? Let's scatter uncomfortable benches or, better yet, eliminate seating altogether. After all, we wouldn't want anyone to get too comfortable and actually spend time in these supposedly public spaces. And why stop there? Let's install fences, gates, and barriers to make it abundantly clear that these parks are off-limits to anyone seeking leisure or enjoyment. Birch Park in Downtown Santa Ana is a great example of a space like this filled with defensive designs such as no bathroom, no benches and a gate around the park. Perhaps we can even add some intimidating signage that warns people to stay away, or police vehicles driving through the park ensuring that the message of exclusion is loud and clear. Oh, and let's not forget the brilliant idea of implementing hostile architecture (described here by journalist Jonny Coleman in LAist). Those pesky skateboarders and homeless individuals might dare to use the park for their activities, so let's install those uncomfortable spikes, armrests, and uneven surfaces to make it virtually impossible for anyone to find solace or comfort within the park's boundaries. Because, really, who needs a thriving, inclusive community when we can have parks that are void of life and energy? Who needs the laughter of children, the sight of families enjoying a picnic, or the simple pleasure of a leisurely stroll when we can maintain the sterile, unwelcoming atmosphere that perfectly aligns with our vision of a park-free utopia? So, let us embrace the genius strategy of City Parks and Recreation, where the motto is clear: "No one is welcome, and we'd prefer it that way." After all, who needs vibrant parks that bring people together when we can have empty, soulless spaces that serve as a constant reminder of our disdain for human presence. California's public parks, with their unequal distribution and car-centric infrastructure, embody a tale of absurdity. It is imperative that we challenge the status quo, prioritizing equity in park planning, community involvement, and active transportation infrastructure. Let us reimagine a California where parks become symbols of inclusivity, nurturing the well-being and connectedness of all residents, regardless of their socioeconomic background or cultural identity. Limited access to parks means limited opportunities for communal gatherings and shared experiences. While New Yorkers revel in the vibrancy of Central Park, Bryant Park or the High Line, where every corner bustles with life and laughter, Californians are left to ponder the irony of their sun-soaked but desolate recreational spaces. The social isolation experienced by many becomes a stark reminder of the missed connections and lost opportunities for community engagement. Madeleine Spencer is the Co-Director of PlacemakingUS and is working towards building social life within public spaces, with emphasis on equity and inclusion. This article is meant to make visible the need for placemaking in California city parks where the co-production of public space with community in parks would including everything from regular community programming, entrepreneurial opportunities through kiosks, public restroom access, movable seating, better lighting and the production of intentional kid friendly spaces, while at the same time alleviating the currently burdensome permitting processes and defensive design tactics used to control the currently derelict spaces. This article is meant to make evident the need for policy changes in the current management of parks within the state of California. Photos by Ryan Smolar and Denise Reynoso

PlacemakingUS, in partnership with CNU Southwest Chapter and The CityBuilding Express (CBX), is excited to announce a grand tour for New Urbanists and placemakers from Washington DC to Charlotte, showcasing 300 years of exemplary developments. The tour will take place from May 28-30, offering attendees a unique opportunity to explore different development types, architectural styles, policy frameworks, New Urbanist and placemaking strategies, and social issues impacting our cities and towns. From adaptive reuse to sustainable development, attendees will visit a range of communities and developments, from college campuses to mixed-use developments, brownfields, and greenfields. Here are five reasons why placemakers won't want to miss this journey: 1. Learn from local experts and leading practitioners who will share their knowledge and insights about each project as we journey 700 miles of roadway. 2. Explore a diverse range of development types and their unique challenges, gaining a comprehensive understanding of how policy, design, place and past intersect in three states and the federal district. 3. Appreciate the wide range of architectural styles and designs that define our urban landscapes, from Neoclassical to Modern, Gothic to Colonial, and Landscape Design and Transportation Design to New Urbanist. 4. Dive into social issues that affect our communities, such as equity/justice, climate change, systemic racism, and democracy/inclusion, and learn about different strategies that have been used to implement new practices and approaches. 5. Network with community leaders, policymakers, architects, planners, and developers from across the country, building valuable connections and exchanging ideas and best practices. Participation in the tour costs range from $795 for single occupancy and $595 for double occupancy including two nights of hotel accommodations, three lunches, bus transportation, snacks, and shwag. Learn more at citybuildingexchange.com.

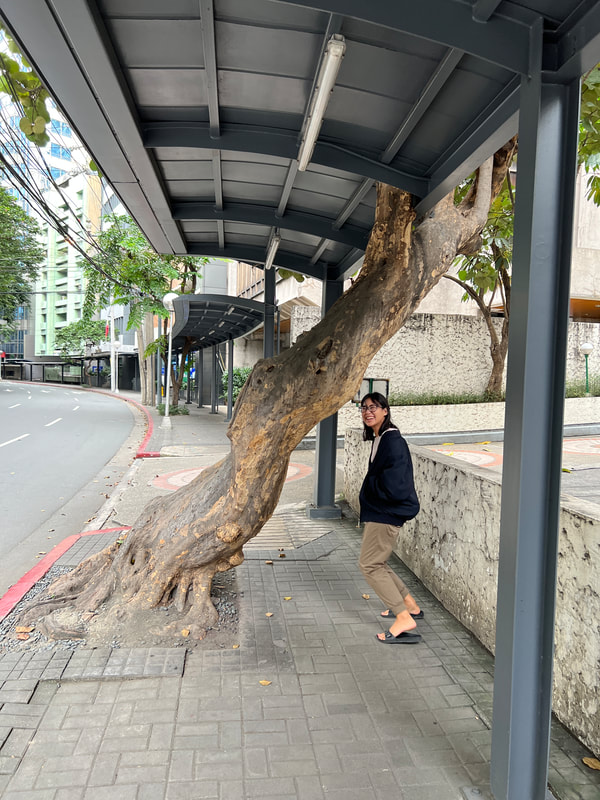

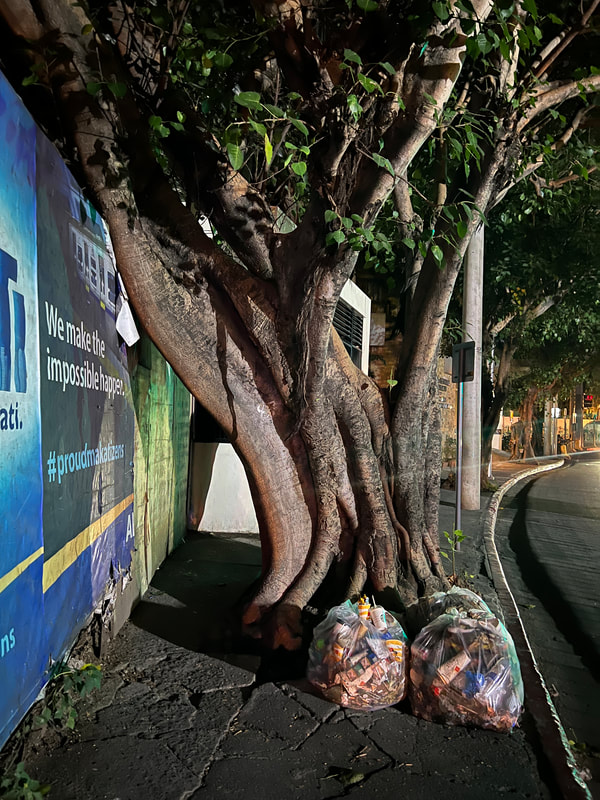

Story by Ryan Smolar In her classic tome, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs eloquently advocated for the importance of sidewalks when she wrote, "Lowly, unpurposeful, and random as they appear, sidewalk contacts are the small change from which a city's wealth of public life must grow." More recently, The Social Life Project, has also recognized the importance of sidewalks, identifying them as one of their critical 11 strategies for creating lively and connected places that promote commerce and community. During my recent travels to various countries, I had the opportunity to experience and document the state of sidewalks and their impact on street life and sense of place. While I did see some positive examples, overall, I was struck by the inadequate and often unsafe conditions that can stifle street life, not only by reducing walkability, but also by causing fatalities due to the neglect of pedestrian needs. In this article, I will compare, contrast and learn from the world beneath my feet. IndiaCrossing the street in India is a colorful experience whether you're in Mumbai, Mangalore or Bangalore. During Placemaking Week India, I visited multiple cities and rural areas, and Ethan Kent of PlacemakingX, cleverly observed that a national campaign for sidewalks would greatly benefit the entire country. Indian placemakers repeatedly highlighted the dangers of road traffic and the attitude that if a pedestrian is injured or killed on the roadways, it is considered their own fault. This issue hit close to home when I learned that one of the event producers of Placemaking Week India, Prahtima Manohar, had lost her own cousin in a roadway accident. Despite the often chaotic nature of Indian streets, one positive aspect is the presence of street-side markets offering fresh fruits, vegetables, and beautiful flower arrangements, as well as the mandala art often found on the ground around temples, which helps create special spaces despite the dangers. Manila, PhillipinesIf sidewalk obstructions were an Olympic sport, Manila would bring home the gold. I never met a street tree I didn't like. Until I met these ones. Cars rule the roads in Manila where new streets lock pedestrians out and force them into underground corridors. What goes down must come up. Pedestrians and cyclists are forced into subterranean hallways in Makata. These slums have eschewed sidewalks in favor of shared streets that are incredibly social, lively places. The sidewalks in Manila exist, but they are so bad, that they seem like a cruel joke at the expense of the ambling citizens of one of the most populous cities of the world. The footpaths are often narrow strips that are comically interrupted by overgrown trees, redundant electric poles, piles of dirt, and the occasional side hustle. Street level crossings in the business district are gated off, forcing pedestrians to use elevated crossings or subterranean tunnels in favor of highway speed vehicular prioritization. Philippine placemakers told us that when they advocate for politicians to prioritize walking and biking infrastructure, they often hear the argument that this type of infrastructure is unnecessary because it takes too long to get around on foot. However, as the placemakers point out, this transportation method would be quicker if it were properly prioritized, creating a vicious cycle of circular logic. Despite the lack of comfortable sidewalks, Manila does invest in floating walkways and ones buried beneath the earth, which may move people around but on monotonous paths that do not contribute to ground-floor vibrancy. On the other hand, when you venture out of the urban core into a neighborhood like Punta Santa Ana, you find that the lack of sidewalks leads people to spread out into all parts of the street, creating an almost closed-off street party feel with people doing karaoke and greeting friends and strangers alike with warm affectations. Drivers move slowly and will honk at you to warn of their presence, and it's just a fun and lively place to be where anything seems possible. SingaporeThese cramped and narrow sidewalks in Singapore are a claustrophobic's nightmare (i.e. Me!). Of all the neighborhoods in Singapore, Little India demands more attention to create more comfortable public spaces. On the plus side: Singapore's covered sidewalks are a joy in sun and rain. Their many park pathways are pure bliss. Haji Lane is delectably right-sized: a pedestrian street dual-lined with restaurants, bars and cafes is a daily street party. Singapore is a wonderful place to walk around, especially in the classic neighborhoods like Tajong Pagar, Chinatown, and Little India, but one issue is the sidewalks are not wide enough to handle the amount of foot traffic. Many of them are covered with colonnade overhangs, an elegantly functional remnant of heritage shophouse architecture, but which makes your walk interrupted by uneven surfaces, as you may have to step down or up unexpectedly, or encounter awkward ramps. In Little India, people use the sidewalks more than any place in the city: people are sitting everywhere, meeting with friends, taking their shoes off and contemplating the jam between their toes, it's like they're at a beach resort sitting on cabanas, but without any accommodations except for their own square inch of pavement from which to perch. This sidewalk scuffle seems particularly egregious seeing as Singapore is one of the best case studies for vehicular congestion pricing. Because their nation adopted forward-thinking urban design principles before car ownership had taken hold, they were able to curtail car dominance through a hefty registration fee that prohibits most from driving in favor of other forms of transportation. This creates the unique and bizarre pedestrian experience of you looking out to a multi-lane road and seeing virtually no car traffic, but then looking at the tiny strip of sidewalk and seeing bodies bumper to bumper and absolutely frustrated. On the flip side, Singapore also does some really wonderful things with sidewalks that should be recognized. I love their covered walkways which make it easier to go the distance in both rain and extreme sunny conditions. These seem to congregate around transportation as well which make them a good use of resources. Also, Singapore has created awesome walkways along the Singapore river. A walk along its banks will lead you to multiple commercial and heritage adaptive reutilizations of their historic river quays, and further upstream you find yourself in recreational forests that seamlessly act as permeable rain catchment systems to sustain the city's water supply. London, UKFinally, a refreshing change of pace. The streets in the center of London are a storybook amusement to walk along. You might encounter a vibrant pedestrian square like the fabled Covent Garden area, which is an entire area purged of cars by attractive, antique pushcarts teeming with horticultural displays. The walk along the banks of the Thames Riverfront is an uninterrupted delight (minus the detour you have to take behind the MI-6 spy headquarters), with deja-vu views of some of the world's most familiar buildings. Architecturally distinct bridges criss-cross the meandering waterway, well-utilized public spaces filled with pop-up markets and temporary art installations buttress your path, and there's even a punctual ferry service powered by Uber to use when your feet start to ache. Unfortunately, this area is quite expensive, luxury-driven and still owned by royal families and the literal aristocracy, but there's something to glean here from the sound proportions and giddy feelings of all the paserrbys. San Juan, Costa RicaPlacemakers working to implement the World Health Organization's Age-friendly Cities Framework in San Juan, Costa Rica's capital, shared their concerns about the status of their sidewalks. According to locals, the policy in place means that each property owner is responsible for maintaining the section of sidewalk in front of their property. While one could optimistically hope this would lead to creative solutions and a pride of ownership, it instead results in a patchwork of inconsistent materials, grades, and conditions, making walking a challenging and uncomfortable experience for many, particularly for the elderly community. JapanJapan is known for its excellent food, trains, and courteous culture, but when it comes to sidewalks, they are falling short these days. During my visit, I noticed a significant increase in the use of bicycles since I was here just before the pandemic. This is great to see, however, Japanese bicyclists are encouraged to ride on the sidewalks, which can make walking a chaotic and dangerous experience. As you're walking down the sidewalk, bicyclists unexpectedly appear, weaving in and out of pedestrians, leaving them spinning in their wake. At night, their bright lights shine in your face, making it difficult to see. It's obvious that Japan is at a critical juncture where the demand for cycling illustrates that it is ready to become a cycling culture like Amsterdam or Copenhagen, but ridership will likely not grow without addressing this backwards approach to placing cyclists and pedestrians at odds. Lessons from the RoadI hope you enjoyed this brief trip around the world. I think it illustrates the universal role sidewalks play in the livability and vitality of a city and how regions can be strong in some aspects of delivering great sidewalks, and weak in others. Here's a few tips from the observations made through this journey:

In conclusion, the importance of sidewalks in cities cannot be overstated. From the bustling streets of India to the patchwork sidewalks of San Juan, it is clear that sidewalks play a vital role in the livability and connectness of a community. Adequate size, maintenance and consistency, comfort, and accessibility are all key factors in creating safe and enjoyable sidewalks for everyone. Furthermore, incorporating unique features such as street level crossings, sidewalk marketplaces, and shared roadways can enhance the overall experience and create a sense of community. I'll see you on the sidewalk. Story and Photos by Ryan Smolar.

The Khmer Rouge genocide caused a mass refugee exodus out of Cambodia that made Long Beach, California home to the largest number of Cambodian people outside of their home country. This underserved diaspora living in central Long Beach is emerging into a thriving neighborhood and business community despite having to fight for access to resources and for environmental, political, linguistic, and economic inclusion. At the heart of the district is The MAYE Center, a unique culture and healing center housed in a 100-year old carpenter-style bungalow on a very busy commercial corridor, making it a sort of open house for trauma-informed community health and healing. Before COVID-19, this sanctuary provided a social space, yoga and meditation, on-site farm and gardens, meal-sharing, and even acted as a small business incubator. Since COVID-19, many of the in-house activities have been curtailed and the MAYE Center has received funding to provide healthy meals for free to neighbors, which they provide partially in the form of gift cards to local businesses to help keep the fragile ecosystem of community markets and restaurants intact. An unexpected lifeline came in the Spring of 2020 as California’s counties and cities began relaxing policies towards outdoor dining and allowing for parking spaces, streets and pedestrian right-of-ways to be converted into safe, outdoor public spaces. In Long Beach, the Open Streets Initiative was launched “to temporarily transform public areas, including sidewalks, on-street parking, parking lots, plazas, and promenades, into safe spaces for physically distanced activity.” Like many similar programs across the state, this successful strategy began benefitting downtown and shorefront business districts, while other parts of town were slow to build outdoor spaces or even consider the benefits such an approach could provide local businesses, community organizations, or those they serve. Long Beach Fresh, the city’s food policy council and CAFPC member, brought in Placemaking US, an organization whose “United Streets of America ‘’ program was working to help equalize access to new outdoor opportunities for non-profit organizations, BIPOC led initiatives, and independent small businesses. The MAYE Center jumped at the opportunity to work on a “healthy flex zone parklet” area along the side of their property which was co-designed with them as a multi-purpose space for food distributions, community meetings and performances as well as a passive space for community gathering and even napping in hammocks. The concepts delivered by architect, Tina Govan, and the MAYE’s agricultural designer, David Hedden, were permitted by the City of Long Beach and the project launched as a Cambodian “Marklet” with a micro-enterprise Cambodian BBQ, juice press, and a street clothing company popping up in addition to free food being donated to the community. This food and place-based project continues to pop-up when local guidelines allow and it is a finalist for several forms of funding to be completed as a more permanent extension of the MAYE Center’s mission to “to help those in our community to cultivate self-healing, resiliency, and wellness through proven, culturally sensitive, and environmentally healthy means” in the community which it serves. After our experience in Long Beach, we argue for the continued openness of authorities to allow for alternative uses of the streets as pioneered by outdoor dining in the pandemic. However, equitable opportunities need to be made accessible for community uses like allowing the MAYE Center to inexpensively and effectively create a flexible outdoor environment. These spaces increase purposeful engagement with the neighborhood and create a healthy “third space” for the community to gather, connect, and build resilience.

We believe the 2020 roll-out of the relaxation of the public-right-of-way has been unequally skewed towards restaurants, especially those in privileged areas with walkable streets and business improvement districts. We hope future legislation and programs will acknowledge the necessary funding, technical assistance, community outreach, and equity of access for a diversity of neighborhoods, local marketplaces, micro-enterprises and vendors, nonprofits, and disadvantaged businesses. Food Policy Councils like Long Beach Fresh and Placemakers at Placemaking US are ready to help. This story was originally published in the 2020 California Food Policy Report. Story by Ryan Smolar. Photos by Brian Feinzimer. |

AuthorsArticles contributed by placemaking experts across the US Archives

July 2024

Categories |

PlacemakingUS

|

PlacemakingUS Newsletters

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed