|

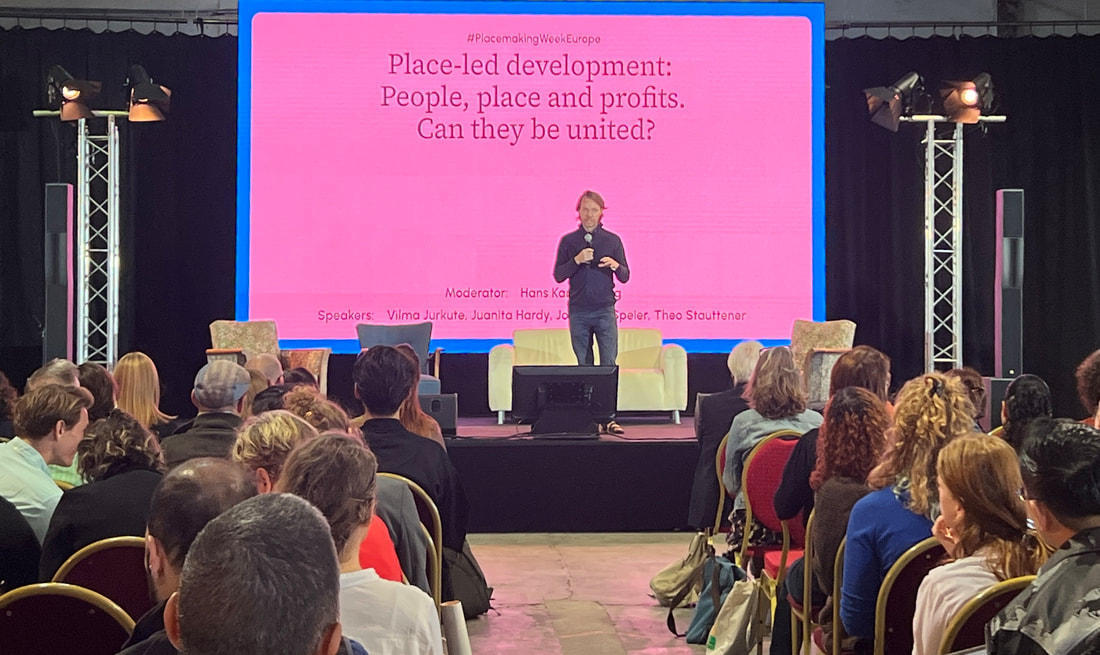

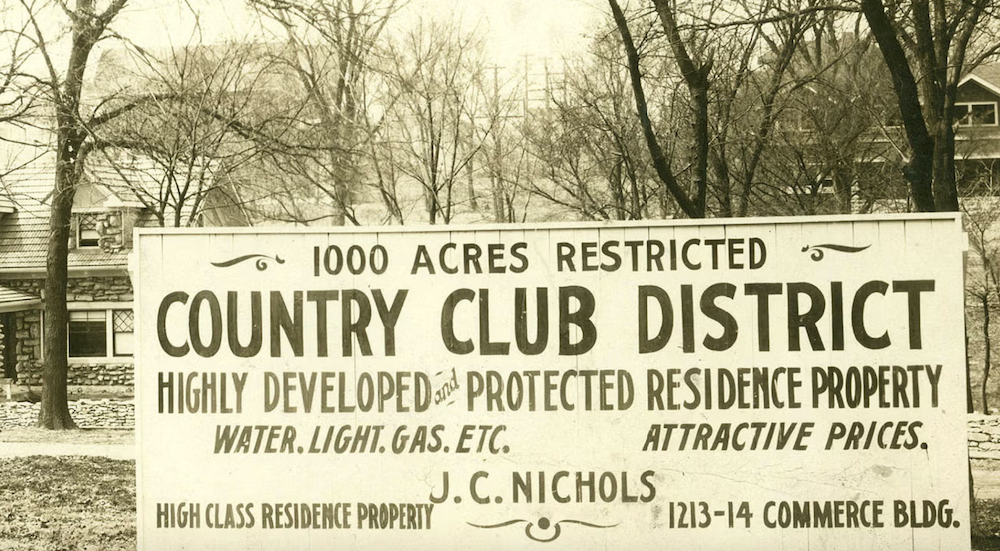

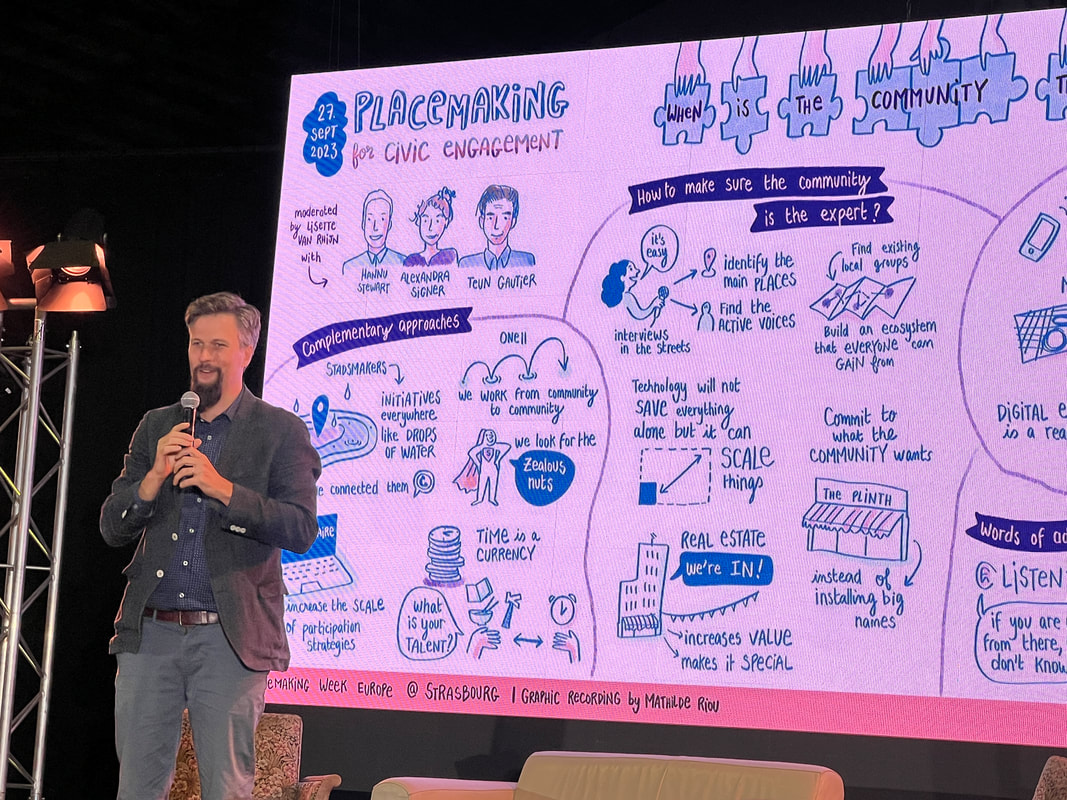

Placemaking, a term with noble intentions in the realm of urban development and community-building, is at risk of losing its true essence. As we grapple with the ambiguity surrounding this concept, there is a pressing need to define placemaking and defend it. Without a clear definition or underpinning principles, the term becomes vulnerable to distortion, manipulation, and misappropriation by commercial and political entities and the uninformed. In this article, we delve into the critical importance of upholding what we mean by the word, 'placemaking' and the consequences of allowing the term to be used willy-nilly. A Most Meaningless Word Recently, an article in Dezeen created ripples within our placemaking community with its deliberately provocative headline: "I have a confession to make: I have no idea what placemaking is." The piece aimed to make a stir and ignite debate, cited the ambiguous language often used to describe the multi-faceted subject by quoting at length from Project for Public Space's lofty explanations of the concept. Unfortunately, the fine-buttered words and finessed phrases from their website do seem to paint placemaking as a panacea that sounds suspiciously like the snake oil salesman's remedy for cities. In response to the grenade Dezeen threw into the room, the co-director of Placemaking Europe penned a response entitled, "I have a confession to make: I don’t care what placemaking exactly is." His article argues that delving into semantics is a futile endeavor when placemaking appears to be an overarching term encompassing individual, positive actions aimed at enhancing our urban spaces. While, in my heart, I'm inclined to agree, this philosophical stance raises concerns—especially for a group that recently brought together 500 placemaking practitioners and eager learners, providing them with content that sought to define placemaking through speeches and interactive workshops. A precarious panel on placemaking at Placemaking Week Europe 2023 in Strausborg, France. The Dangers of (Mis)Defining Placemaking At the Placemaking Week Europe event last month, I found myself stunned at what was being described as placemaking from their main stage. During a talk entitled, Place-Led Development - People, place, and profits. Can they be united? an elderly woman of color named Juanita Hardy, who is the Senior Visiting Fellow for Creative Placemaking for Urban Land Institute, had this to say: "Placemaking started in the United States in the 1920s when a developer in Kansas City built a successful shopping mall 4 miles from the downtown heart." Besides what sounds obviously wrong with that statement, I knew as one of the few Americans in the room who's been to Kansas City several times that she was referring to County Club Plaza and its creator, JC Nichols. While Country Club Plaza is a charming piece of faux urbanism with a mix of automobile access, walkability, and even great programming, this project is more notably the development where suburban racial segregation took root in America. A recent article in Slate called, "The Made Who Made the Suburbs White" more accurately describes the Country Club District, not for its placemaking principles but for its pioneering of the use of racial covenants: not allowing minorities to rent or buy in the district. The Country Club's "protected" district was a progenitor of the racially-segregated suburbs. Photo courtesy of The State Historical Society of Missouri To quote the Slate article at length: "In the 1930s, the Nichols Way received a boost from the federal government...To Kevin Fox Gotham, a professor of sociology at Tulane University and author of Race, Real Estate, and Uneven Development, it seemed as if the Federal Housing Authority had “adopted [Nichols’] methods and practices almost verbatim.” This means there is a strong connection between the racial covenants that JC Nichols pioneered with the federal practice known as redlining, which segregated and destroyed black neighborhoods across the country. JC Nichols should be remembered as the father of racial strife, white flight, and our national inequities, but not the father of placemaking without the caveats that we now have federal laws like the Community Reinvestment Act and Fair Housing Act to protect people who look like Juanita and me against the ideas and actions of men like him. The Line is a futuristic, 'sustainable' megacity project in Saudi Arabia that aims to create a 170-kilometer-long, car-free urban development in the desert. The project has produced a mini-series calling the architects, planners and futurists associated with the plop project as "The Line's Placemakers." Letting Commercial Interests and Professionals Define Placemaking In 2021, PlacemakingUS was approached by Ph.D.'s at the research department of a global architecture firm asking us to endorse a report they made to educate their 1,000 employees on "The Subtle Art of Placemaking." But after reading it, I had to write them a pointed rebuke that their report should rather be called "The Subtle Art of Placebaking," i.e. taking the ingredients of placemaking and utilizing them in a measured, professional and controlled way to bake a pre-packaged "place cake." Notably because their guide lacked any mention of co-design or community participation, failed to explore the use of the temporary to inform permanent solutions, neglected discussions of sustainability and equity, and omitted fundamental concepts like the mixing of uses. Another group, the International Downtown Association (IDA), has recently become an accrediting organization. They have introduced the suffix "LPM" to designate "Leadership in Place Management" to those bold enough to pass a 100-question multiple choice test. One of the core domains of knowledge for this accreditation is about placemaking expertise. While the information promoted by IDA maintains high quality and is crowd-sourced, it is primarily driven by the commercial interests of individuals representing business and property owners. I've encountered numerous business improvement districts (BIDS) whose idea of placemaking is constructing outdoor ice skating rinks in arid and subtropical regions of the United States. While these novel gimmicks inject fun and vitality into cities, they often disregard the fundamental principles of sustainability, including water use, energy consumption, non-renewable materials, and transportation costs on the environment. These projects reveal the trend that BID placemakers are often just re-branded marketing/events staff whose motivations are to follow trends and attract customers, rather than to ensure that the city remains accessible for everyone to contribute creatively. Kady Yellow, a distinguished practitioner, bucks this trend by demonstrating that a BID-embedded placemaker can serve as a powerful catalyst for driving systemic change and amplifying diverse voices. Through her roles as the Director of Creative Placemaking in both Flint, Michigan, and Jacksonville, Florida, she has illuminated the transformative potential of resident-led placemaking programs within business districts. Her initiatives not only educate the community about their role as placemakers but also provide essential funding and leverage the BID's unique privileges, granting access to permits, spaces, and relationships for collaborative city-building. Similarly, Richard Amore at the Vermont State Department of Commerce worked with his state legislature to create crowd-matched funds to make community-led and supported placemaking initiatives more accessible through the a 2:1 match of local funds raised for their own ideas to make their communities into Better Places. A business improvement district building a temporary, outdoor ice skating rink in sunny Southern California as a "placemaking" project. This wood was cut just for the project, but boosters say it will be re-used for 5 winters. To Define AND Defend Ethan Kent, leader of our PlacemakingX global networks, often upholds the ooey-gooey consistency of the made-up word placemaking saying there's great power in letting people define placemaking for themselves and the plasticity of the definition lends to the field's necessary adaptability. As an idealist, I agree, but the realist side of me recognizes that as we let placemaking blow in the wind, other interests are defining it and giving it a bad name such that many low-status communities now prefer the term placekeeping, that is keeping the so-called placemakers away so that the neighborhood can continue to exist without cultural and physical displacement. This issue takes many forms, as even our sister network, Placemaking Collective UK, is considering changing their name to be called the Place Collective UK, due to the perceived 'wonkiness' of our term. They were advised to keep placemaking in their name, yet another network, Peacemakers Pakistan, has struck a unique balance by alluding to placemaking while adapting their name to the most relevant challenges and opportunities of their context. A good example of the need to define and defend placemaking can be illustrated by the National Endowment for the Arts-funded white paper "Creative Placemaking" published by Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa in 2010, which set the stage: "In creative placemaking, partners from public, private, non-profit, and community sectors strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood, town, city, or region around arts and cultural activities. Creative placemaking animates public and private spaces, rejuvenates structures and streetscapes, improves local business viability and public safety, and brings diverse people together to celebrate, inspire, and be inspired." This report, which has been cited nearly 700 times in further works, helped define that field and resulted in over a hundred million dollars of investment into that subset of placemaking. Effectively to this day, you're more likely to search for the phrase 'creative placemaking' than just 'placemaking' according to research shared at Placemaking Week Europe. Even so, I visited Denmark's national center for design last year and learned their definition of creative placemaking was limited to the adaptive reuse of industrial space for creative industries. Hmmm...I would categorize that as adaptive reuse within the realm of the creative economy, but it is nowhere near encompassing what creative placemaking is about or why it's essential for society and public spaces. The Danish Design Center is not only teaching design for cities in Denmark, but is promoting their approach to leaders of cities and countries all over the world. We have to make sure we're visiting institutions and events promoting placemaking to ensure they're connected to the canon of knowledge that they're eagerly espousing. Graphic recording of the shared definition of placemaking at the 2023 Placemaking Week Europe conference. The Middle Road Forward: Balancing Education, Contribution and Innovation So, how do we define placemaking? Well, there are many shoulders to stand on, and a multitude of sources have contributed to our understanding. We have the insights of Jane Jacobs, the work of William H. Whyte and the Project for Public Spaces, the enlightening Social Life Project blogs, the empowering concept of the Right to the City, the global significance of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals and New Urban Agenda, Mike Lydon and Tony Garcia's illuminating book Tactical Urbanism, the equity frameworks championed by Mindy Fullilove, Majora Carter, and Blackspace, the refinements on architecture by Christopher Alexander and Jan Gehl, the community-building concepts of John McKnight and Peter Block, the health-oriented social infrastructure explored by Donald Appleyard and Erick Klinenberg, and countless other sources that have provided a solid foundation for our understanding. In fact, we've recently started compiling a list of books on placemaking for an American Placemaking Library and have already amassed over 100 titles spanning economics to urban planning, all of which contribute to the rich tapestry of ideas that shape the concept of place and placemaking. Our task is to ensure that we promote the "first principles" of placemaking and maintain an ongoing dialogue to evaluate and question what placemaking means, both on a global scale and within local contexts. As part of the PlacemakingUS network, we commit ourselves to learning and sharing the best and most useful knowledge we encounter with local practitioners throughout the country. We achieve this by engaging in visits, learning programs, and by actively participating in discussions wherever we're welcomed. We seek the support of our local partners, funders, and like-minded firms who share our belief in the wisdom of Jane Jacobs: "Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody." In an era where placemaking is at the forefront of urban development discussions, it is imperative that we do not leave its definition to chance. Failing to define placemaking, even to some degree, leaves it vulnerable to distortion and exploitation by those who may not have the best interests of our communities at heart. Let us remember that clarity in our understanding of placemaking is not just an intellectual exercise; it's a safeguard for the future well-being of our neighborhoods and cities. Op-ed by Ryan Smolar

Initiator, PlacemakingUS

1 Comment

|

AuthorsArticles contributed by placemaking experts across the US Archives

July 2024

Categories |

PlacemakingUS

|

PlacemakingUS Newsletters

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed